Note: This is Part III in a series of Distilled History posts I am writing about one of the most remarkable St. Louisans to ever live, James Buchanan Eads. Part One, which details caisson disease during the building of Eads Bridge, can be found here. Part II, which gives a brief introduction to his life, can be found here.

Also, Distilled History now has a Facebook page. Please give it a “Like” to see the stuff that doesn’t make the blog, random St. Louis history tidbits, and of course, my own musings on drinking good cocktails.

![]()

My delightful “Summer of Eads” rolls on.

Without a doubt, I have had a good ‘ol time getting to really know James Eads over the past few months. But I’ll also confess that he’s put me in one hell of a pickle. He’s an overwhelming subject to write about. Try as I might, I have struggled mightily trying to cram all of his accomplishments into a few boozy blog posts.

Furthermore, he’s a tough guy to drink with. I’ve scoured the streets near his bridge, where his glass factory stood, where his gunboats were built, and where his mansion sat. No bar or cocktail idea was born from any of these searches. Unless I devised my own “Eads Cocktail” (which would probably need to include river water), I was out of luck.

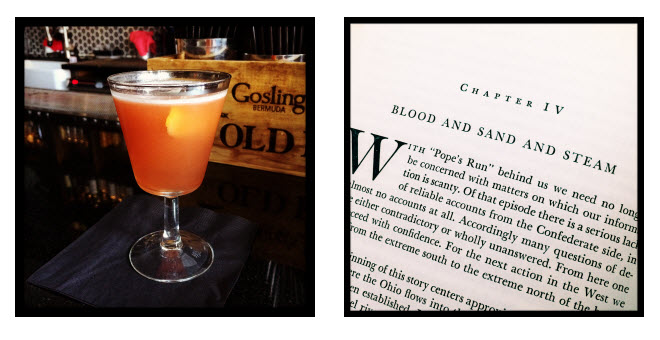

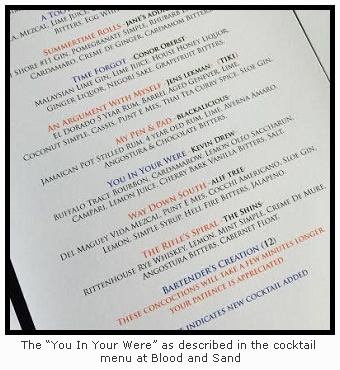

But I can always find a reason to drink. It’s just that I’ve never stumbled into one like I did for this post. It happened after picking up (several more) books about bridges, gunboats, and diving bells at the St. Louis Central Library. I then settled in at one of my favorite barrooms to read about what else James Eads had his hands in. As I ordered my drink, I flipped open a book titled Guns on the Western Waters by H. Allen Gosnell. I searched the index to find out where James Eads shows up, and it directed me to a chapter that made me do a double-take. The title of the chapter was nearly identical to the name of the bar I was sitting in at that exact moment.  What a tasty coincidence that I found myself reading Blood and Sand and Steam while drinking a delicious cocktail in Blood and Sand. And there ya go, my drink problem was solved.

What a tasty coincidence that I found myself reading Blood and Sand and Steam while drinking a delicious cocktail in Blood and Sand. And there ya go, my drink problem was solved.

As I sipped my delicious cocktail (the “You in Your Were”), I dove into the next remarkable chapter of Eads’s life. I was excited, because before I became a big St. Louis history nerd, I was a big Civil War history nerd (just two of many reasons). I’m also solidly pro-Union. I have no patience for any of that pro-Confederate nonsense people spout these days, so I was thrilled to learn that James Eads felt the same way in his time that I do in mine.

At the outbreak of the war, James Eads was only forty-one years old. He was retired, extremely wealthy, and a well-respected man in St. Louis. He was done with salvage work, but innovation and the Mississippi were never far from his mind. From his stately Compton Hill mansion, he found himself free to brew up a few ideas in order to help the good guys win the Civil War.

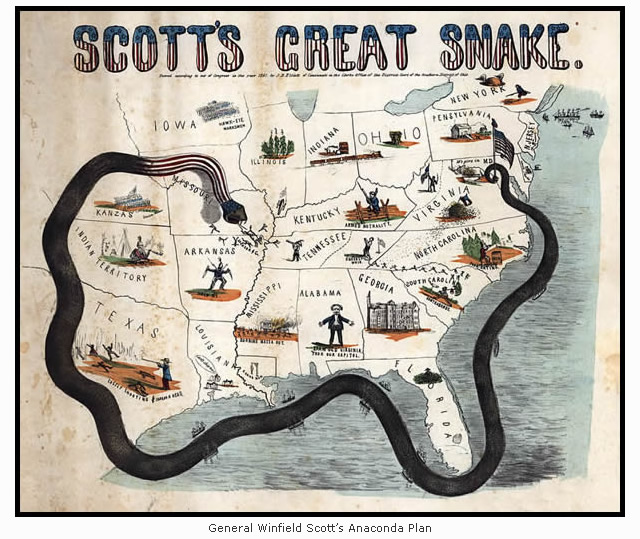

James Eads knew the western rivers would play an important strategic role in the upcoming conflict. Notably, control of the Mississippi River was a key component of Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan, a naval strategy devised to blockade and squeeze the Confederacy like a coiled snake. Like General Scott, Eads believed that if the Union controlled the Mississippi from New Orleans to St. Louis, it would ultimately control the western theater of the war. If it succeeded, the Confederacy would be effectively severed in two.

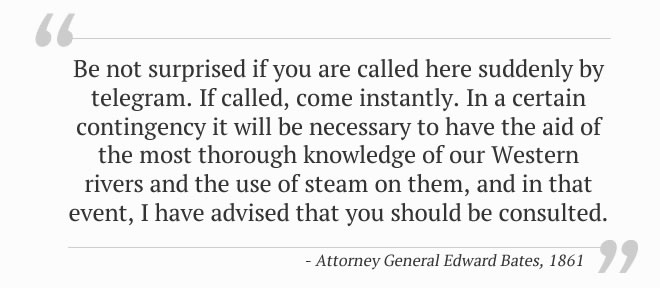

Abraham Lincoln realized this as well, referring to the Mississippi as the “backbone of the rebellion” and the “key to the whole situation”. Just days after Fort Sumter was fired upon in April 1861, James Eads received a letter from Edward Bates. A former Missouri Congressman and friend of Eads, Bates had recently been named as Attorney General in Lincoln’s cabinet.

It was the letter he’d been waiting for. Prior to the war, Eads had already been lobbying politicians and war strategists to let him help. His reputation as a river man preceded him, so it wasn’t long before Eads found himself in Washington D.C. reviewing river strategy with Lincoln’s cabinet. While there, he enthusiastically backed a proposal to build a fleet of gunboats that could help conquer the lower Mississippi. Soon after, the plan evolved into building a flotilla of ironclad gunboats, a type of military vessel never before seen in the western hemisphere.

It was the letter he’d been waiting for. Prior to the war, Eads had already been lobbying politicians and war strategists to let him help. His reputation as a river man preceded him, so it wasn’t long before Eads found himself in Washington D.C. reviewing river strategy with Lincoln’s cabinet. While there, he enthusiastically backed a proposal to build a fleet of gunboats that could help conquer the lower Mississippi. Soon after, the plan evolved into building a flotilla of ironclad gunboats, a type of military vessel never before seen in the western hemisphere.

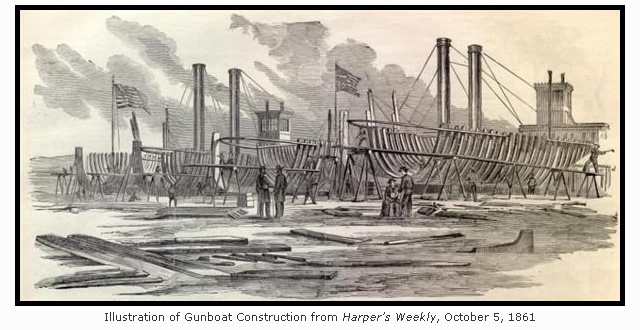

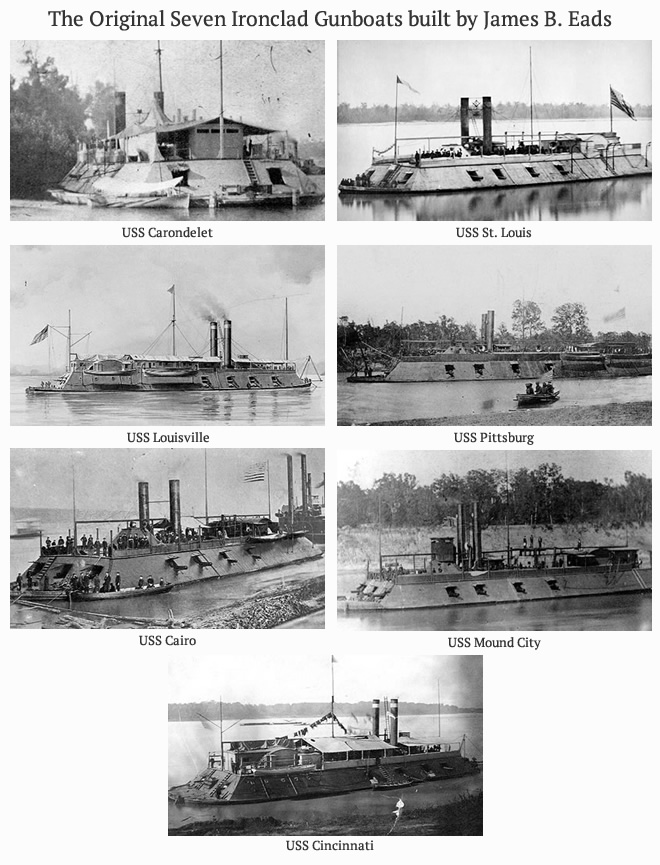

Eads took full advantage of the opportunity. As bids for the project opened on August 5, 1861, Eads submitted a bold proposal, easily winning the government contract. Two days later, he signed a contract stipulating that he’d deliver seven ironclad gunboats at a cost of only $89,600 each. Remarkably, he promised they’d ready to go in only sixty-five days. He was so confident in his plan that he even agreed to pay a hefty fine of $250 per boat for each day it was late.

With a due date of October 10, 1861, Eads went right to work. He contracted with foundries, sawmills, and forges in several states, instantly putting thousands of men to work around the clock. His primary base of operation was the Union Iron Works, a shipyard Eads leased to the south of St. Louis in the village of Carondelet. It was here, near the point where the River Des Peres flows into the Mississippi, that the first ironclad warships ever constructed in the United States came to be.

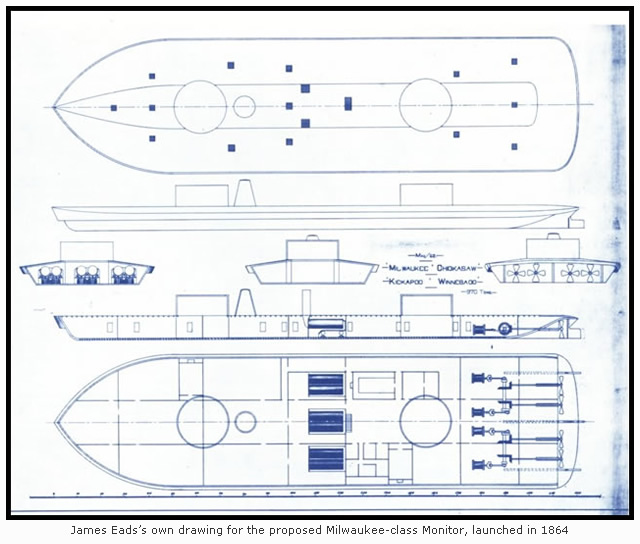

The ships were built, but not designed by James Eads. Although Eads would make significant design improvements to ironclad construction as the war progressed, the first seven were designed by an engineer named Samuel Pook. Named “Pook’s Turtles” because of the resemblance they took in the water, the first ironclads were like nothing that had been seen before. At 175 feet long and 51 feet wide, the boats squatted low in the water. Each was armed with thirteen cannon poking out of sloped wooden sides covered with 2-1/2 inch iron plate. A crew of 175 manned each gunboat.

Due to financial delays and design issues, Eads didn’t meet his self-imposed deadline of October 10. It wasn’t for a lack of trying. Using his own wealth to finance the project, he nearly bankrupted himself while government financing lagged behind. Fortunately, financing was resolved, all late fees were repaid, and the seven “City-class” gunboats, as they were known, were delivered by mid-November. Each was commissioned into the War Department’s Western Gunboat Flotilla in January 1862.

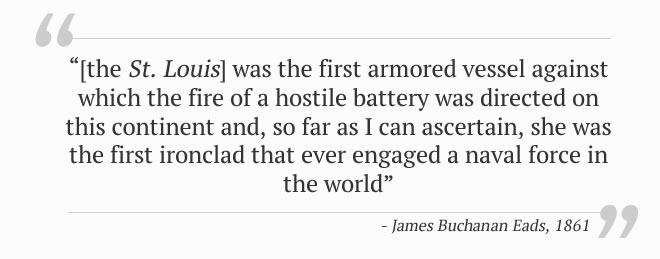

The first was the Carondelet, which slid into the Mississippi River on October 12, 1861. It was the first ironclad built in American history, completed three months before the Monitor, it’s more famous cousin in the east. The St. Louis rolled off just a few days later, and it would plant its own stake in history. After engaging Confederate timberclad gunboats at the Battle of Lucas Bend in January 1862, James Eads boasted about the event in a letter he sent to Abraham Lincoln:

The Carondelet and St. Louis were soon followed by the Louisville and the Pittsburg. To maximize production, Eads had the other three built at a second shipyard in Mound City, Illinois, located about 150 miles south of St. Louis. There, the Cincinnati, the Mound City, and the Cairo rounded out the fleet.

The Carondelet and St. Louis were soon followed by the Louisville and the Pittsburg. To maximize production, Eads had the other three built at a second shipyard in Mound City, Illinois, located about 150 miles south of St. Louis. There, the Cincinnati, the Mound City, and the Cairo rounded out the fleet.

In addition to City-class gunboats, Eads contracted with the government to have several of his own salvage boats converted to ironclads. The Benton, previously known as Salvage Boat No. 7, was commissioned into the Western Gunboat Flotilla in February 1862. Weighing over 1,000 tons and armored with thicker 3-1/2 inch iron plate, the Benton was much larger than the original seven. It would become the most powerful boat in the western theater of the Civil War.

In addition to City-class gunboats, Eads contracted with the government to have several of his own salvage boats converted to ironclads. The Benton, previously known as Salvage Boat No. 7, was commissioned into the Western Gunboat Flotilla in February 1862. Weighing over 1,000 tons and armored with thicker 3-1/2 inch iron plate, the Benton was much larger than the original seven. It would become the most powerful boat in the western theater of the Civil War.

Each of the gunboats would make a significant impact in the western theater of war. Tough and reliable, the ironclads could fire away at close-range while the thick iron plating protected them from returning fire. Although the gunboats were slow and susceptible to mines, shells from Confederate shore batteries dealt minimal damage. The plating caused cannon fire to bounce harmlessly off the angled sides. Even before the boats were launched, Eads had the durability of iron siding tested at his shipyard in Carondelet. Successfully deflecting cannon fire from as close as 200 yards, Eads must have known that he was building the navy of the future.

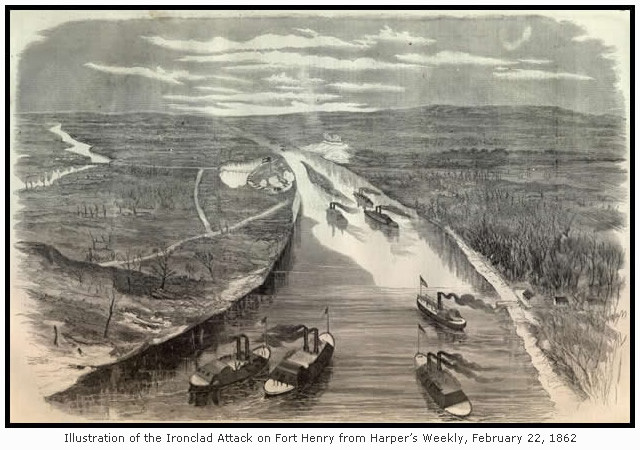

The military success of Eads’s gunboats would be immediate, and they would help launch the career of the Union’s greatest general. At the Battle of Fort Henry in February 1862, the ironclads played a major role in the first significant Union victory under Ulysses S. Grant. Deemed “a victory exclusively for the gunboats” the bombardment from the Cairo, St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Essex (another converted Eads salvage ship) was so effective that the Confederate garrison surrendered before Grant’s land force even arrived on the scene.

The military success of Eads’s gunboats would be immediate, and they would help launch the career of the Union’s greatest general. At the Battle of Fort Henry in February 1862, the ironclads played a major role in the first significant Union victory under Ulysses S. Grant. Deemed “a victory exclusively for the gunboats” the bombardment from the Cairo, St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Essex (another converted Eads salvage ship) was so effective that the Confederate garrison surrendered before Grant’s land force even arrived on the scene.

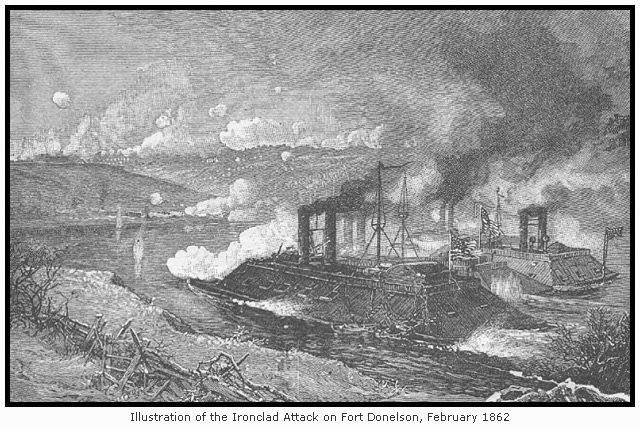

Soon after, the St. Louis, Carondelet, Louisville and Pittsburg aided Grant in taking Fort Donelson. With his famous demand for “Unconditional Surrender” in the aftermath of this battle, Grant’s reputation as a fighter soared. Furthermore, with the help of Eads’s gunboats, two major tributaries of the Mississippi (the Cumberland and the Tennessee) were now open to the Union.

It wouldn’t stop there. As the war progressed, Eads relentlessly worked at improving ironclad design. With his shipyards working around the clock building more ironclads, he included turrets like those found on the Monitor, built boats that drew less water, and continued to improve the effectiveness of iron armor. He also built lighter boats, including a series of “tinclads” that were faster and more maneuverable, but could still withstand musket fire. By the end of the war, his Union Marine Works in Carondelet would produce more armored warships than any other shipyard during the Civil War.

Finally, on July 4, 1863, the Anaconda Plan became a harsh reality for the south. Again aided by Union ironclads, the final Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi surrendered to Union forces. Vicksburg’s fall came just one day after victory at Gettysburg in the east. The war for the river had been won in the west.

The Confederacy was cut in half, and it was made possible by the gunboats James Eads built.

I’ve already mentioned the drink I found for this post, so there isn’t much else to say other than Blood & Sand is (again) one of the best places to drink great cocktails in St. Louis.

I’ve already mentioned the drink I found for this post, so there isn’t much else to say other than Blood & Sand is (again) one of the best places to drink great cocktails in St. Louis.However, I want to mention a menu theme that I particularly enjoy. They name their cocktails after songs. Even better, most of them seem to be named after bands and musicians I listen to often.

I may need to ask TJ and Adam at Blood and Sand (two of the friendliest guys around) to help me out if I ever write about the rich musical history of St. Louis. I’m sure a “Maple Leaf Rag” or a “Birth of the Cool” cocktail would fit nicely on their menu.

But before I get to thinking about Scott Joplin or Miles Davis, I need to close out my Summer of Eads. There’s a particular bridge that needs a closer look.

![]() Sources invaluable to this post (other key sources also listed in Part I and Part II of the Summer of Eads):

Sources invaluable to this post (other key sources also listed in Part I and Part II of the Summer of Eads):

- Civil War St. Louis by Louis S. Gerteis

- James B. Eads The Civil War Ironclads and His Mississippi by Rex T. Jackson

- Guns on the Western Waters by H. Allen Gosnell