Just last week, I finished my first year as a volunteer docent at the Campbell House Museum in downtown St. Louis. I’m pleased to say that joining the Campbell “family” was a great decision. I have met some great people who share similar interests. I’ve learned the fascinating story of the Campbell family and the house they lived in for eighty-four years. And now, I actually get to talk about history to people who want to hear it (unlike many of my good friends who are forced to suffer through it).

I’ve also learned how to give tours and be a quality docent. I didn’t expect it, but I quickly learned that all tours are different based on the museum visitors taking them. Now, when I start a tour, I know within three minutes if I’ll have a two-hour tour with tons of questions and interaction, or a half-hour tour filled with nothing but my own voice. In those first three minutes, I’ll know how to adapt the tour to the people in front of me.

In other words, I now know how to deal with people who don’t give a shit.

I learned early on that If there are small children on the tour, get through the house fast. If not, a meltdown could happen by floor three. A droopy-eyed guy that’s been dragged there by his girlfriend? Skip the chit-chat about intricate carvings on the parlor furniture. I’ve even had a couple of visitors that couldn’t speak English. Since I can’t speak a lick of German, it’s no use trying to explain to Klaus that Robert Campbell made his fortune in the fur trade.

Despite the multitude of differences each tour can bring, there’s one item in the house I never skip. When I bring visitors into the head servant’s bedroom on the second floor, I always stop and point out the small washtub that sits in the corner. Then, I describe the effort it took to use it and take a bath in 1885. When I do, even the most aloof visitor (except maybe Klaus) finds it interesting.

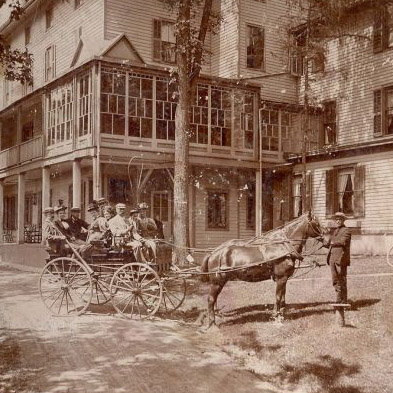

It’s difficult to overstate the malodorous condition of St. Louis in the late 19th century. If you lived in this city 125 years ago, you probably reeked. The people around you reeked. Even the air you breathed and the water you drank reeked. Being one of the largest and most densely populated cities in the country, St. Louis was congested, filthy, and fetid. The air was filled with soot, streets were filled with horse manure, and noxious fumes wafted from inadequate methods of waste disposal.

For the common citizen, the process of getting clean in that environment was difficult and it happened rarely. To use a washtub like the one on display at Campbell House, several trips to a water source were needed to get it filled. Water was lukewarm at best, especially if the bather wasn’t first in line. On bath days, families shared the same tub and the same water.

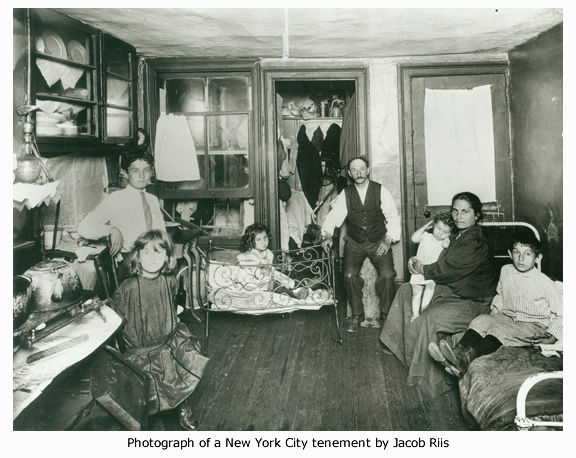

Grime was especially noticeable in the slums and tenements of urban American cities. In St. Louis, a survey taken in 1908 showed that in the poorest neighborhoods, only one bathtub existed for every 200 residents. In the densely populated tenements where more than a quarter of the population lived, one bathtub existed for every 2,479 residents. To make matters worse, bathtubs were not always used for their intended purpose. Due to the limited space in small living quarters, bathtubs often held coal or firewood. Even as late as 1950, only 1/3 of the homes in the poorest neighborhoods of St. Louis had private bath facilities.

Toward the end of the 19th century, social reformers led a movement to improve the quality life of all Americans, not just the wealthy. At the center of this movement was a push to improve the living and working conditions for poor people living in urban slums. Since being dirty and being poor were seen as going hand in hand, promoting cleanliness became a part of that movement.

At the same time, scientists and doctors were figuring out that good personal hygiene could help prevent the spread of disease. This sentiment can be seen in a statement made by the New York Tenement House Committee in 1894:

“Cleanliness is the watchword of sanitary science and the keynote of the modern advice aseptic surgery. If it apply to the street, the yard, the cellar,the house and the environment of men it most certainly should apply to the individual.”

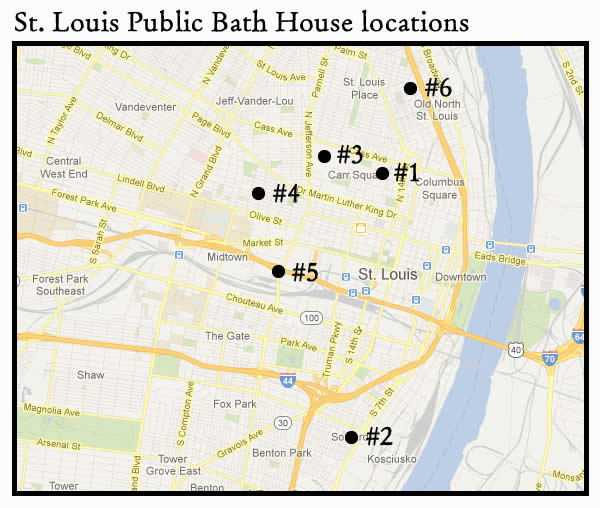

Already popular in Europe, the movement prompted a few American cities such as New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore to build public bath houses in the early 1890’s. Encouraged by the initial success and high attendance rates, the public bath movement quickly spread to other American cities. In St. Louis, the progressive mayor Rolla Wells campaigned for several bath houses to be built throughout the city. Despite his support, it would be several years before St. Louis joined the movement. Forty American cities had operational public baths before St. Louis opened its first.

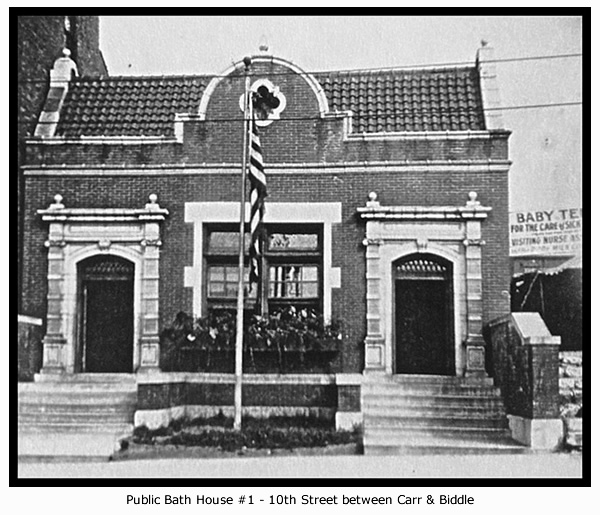

That day came in August 1907, when Public Bath House No. 1 opened near the intersection of Carr and 10th in north St. Louis city. Over the next thirty years, St. Louis would build five more.

Public Bath House No. 1 contained forty-one showers and one tub bath for men. Strictly divided by separate entrances, the women’s side of the bathhouse had fifteen showers and two tubs. Using the baths were free, but soap and a towel could be rented for one cent if a visitor did not bring their own. Modest bathers could even rent a bathing suit if they so desired.

Inside the bathhouse, an attendant sat behind a booth and issued numbered tickets to people as they entered and waited in line. When their number was called, the visitor would walk down a corridor to a cubicle that was divided in two. One side contained a dressing area with clothing storage. The other side contained the shower. Although a time limit existed only during high volume hours, the attendant on duty had full control off water usage and water temperature.

Public Bath House No. 1 was an immediate success. Sixty-nine thousand people visited in the first year alone. By 1915, that number rose to nearly 500,000. Two years later in 1909, Public Bath House No. 2 opened in the Soulard neighborhood. In No.2’s first year of operation, an astounding 238,000 patrons visited the south city bath. Over the next few years, that number would triple.

Unexpectedly, the bath houses became social centers. While queued to get clean, St. Louisans used the locations as a place to socialize with friends and neighbors. The bath houses were considered safe, clean, and pleasant to use. Due to the cavernous echos created by ceramic tile, local newspapers reported prolific singing and choir boys practicing hymns. However, not everyone considered the constant melodies to be music to their ears. In 1951, bath house attendants bitterly complained that the endless renditions of The Weavers’ popular hit, Goodnight Irene, were driving them crazy.

Saturdays were the busiest days, but the early hours of Sunday is when the bath house lines were longest. Following the sentiment that “Cleanliness was next to Godliness”, many St. Louisans made sure get clean before heading off to church.

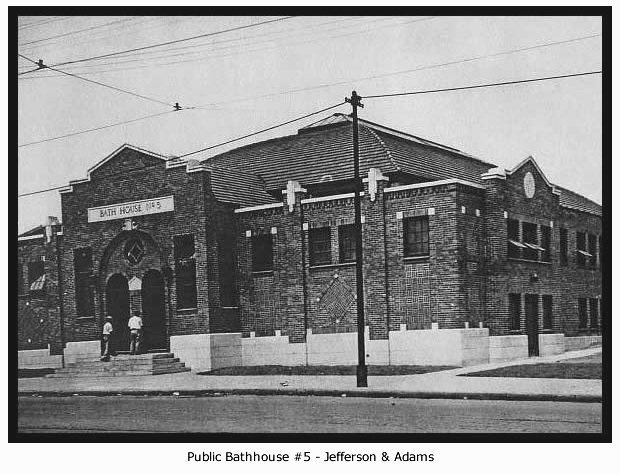

Additional bath houses continued to be constructed in densely populated neighborhoods. In 1910, Public Bath House No. 3 opened just twelve blocks west of bath house Bath House No. 1. That same year, Public Bath House No 4 opened at 3600 Lucas. When St. Louis passed a segregation ordinance in 1916, Bath No. 4 had the distinction of becoming the first segregated bath house in St. Louis. In 1932, a second segregated bath, Public Bath House No. 5, opened at the intersection of Jefferson and Adams.

In 1937, the final public bathing facility was built at 1120 St. Louis Avenue in north city. It serviced 170,000 patrons in the first full year of operation. It would be the last public bath house constructed in St. Louis and the last one to remain open. It’s also the only one of the original bath house buildings that still stands today.

As the 20th century progressed, technology continued to make the process of bathing simpler. In the 1920’s, the cast iron bathtub coated with porcelain began to be mass-produced. The end of World War II brought in the housing boom and the mass flight to the suburbs. It became standard for homes to be built and refitted with private bath facilities. By the 1960’s, the need for public bath houses had all been eliminated. The final facility to remain open in St. Louis, Bath House #6, ceased operations in 1965.

Municipal Bath House #6 still stands today at 1120 St. Louis Avenue in north city. It likely goes unnoticed by the vast majority people who drive near it in order to visit a St. Louis landmark just up the street, the famous Crown Candy Kitchen.

Well, here’s a post I really struggled to find a drink for. How does one tie drinking to a bath house? Even with the thousands of bizarre cocktail recipes and names that exist today, few have any sort of reference to getting clean. The best I could do is when a Google search found a cocktail named the “Naked on the Bathroom Floor”. It includes shots of tequila, Rumple Minze, Jägermeister, Wild Turkey, Goldschlager, and cinnamon schnapps served on the rocks in an old-fashioned glass. Obviously, this drink is meant for people who plan to end up like its name.

Well, there’s no way in hell I’m going near a potion like that. So, I turned my attention to finding a watering hole located near one of the original bath houses. This turned out to be an easy solution. Sitting at the corner of 7th and Soulard, the same intersection where Public Bath House #2 once stood, is Soulard’s Restaurant and Bar. I’ve been to Soulard’s before to try their bread pudding during the Taste of Soulard event, but I had never ordered a cocktail there.

The interior of Soulard’s is attractive and they have a well stocked bar. I ordered my standard Manhattan cocktail to see what I’d get. I ordered it with Maker’s Mark, but I did not provide any further instruction.

They served it straight up in a cocktail glass with a good 2:1 ratio of bourbon and sweet vermouth (I did not see which brand of vermouth was used). It was shaken (sigh), but no big deal. I was happy to get it straight up.

NOTES: A big boost to my research for this post was provided by two sources. First, the Central Library in downtown St. Louis finally reopened. After two years, I was finally able to walk back into that wonderful building. The new “St. Louis Room” simply blew my mind. Writing this blog just got much easier.

Second, the fine people at Landmarks Association of St. Louis again went above and beyond. I called Landmarks for some help, and when I showed up, they had a stack of articles, clippings, and books ready for me to look through. My initial goal was just to find where the original six bath houses were located, but they provided much more. Notably, Landmarks set me up with an article from the Fall 1989 issue of Gateway Heritage magazine titled “The Politics of Public Bathing”. It became the main source of much of the information in this post. If you read this blog regularly, please consider becoming a member of Landmarks or donating to them. They are a wonderful organization that strives for historic preservation in St. Louis.

Good read! I really enjoyed this.

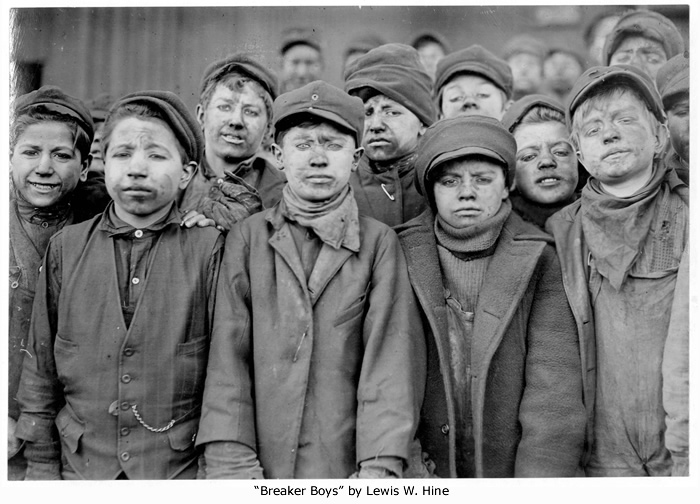

Found this when reading The Campbell House FB page. Great article that I have shared on my Discover St. Louis FB page as well as sharing with the PTGA (Prof Tour Guide Assn) of Metro St. Louis. Our January meeting was at the Central Library and it was quite a tour. Yes, the St. Louis room, and it’s most valuable asset, librarian Adele, was incredible. Thanks for a wonderful comprehensive article. BTW, my husband’s great grandfather worked as a breaker boy in the coal mines of Pennsylvania. He had been orphaned and the family that intermittently fostered him would take him out of the orphanage to work and then return him when there was no work. No one was a child in this era, only a small person meant to work. But he made lemonade out of lemons and started his own mining crew with men working for him.

interesting read—will keep eye out for bath house no 6 when visiting crown candy