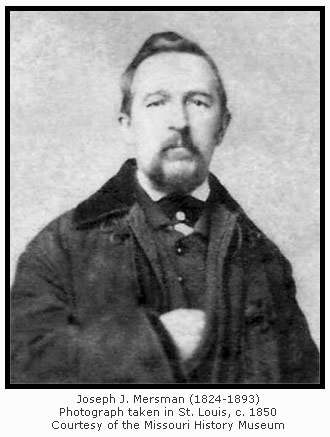

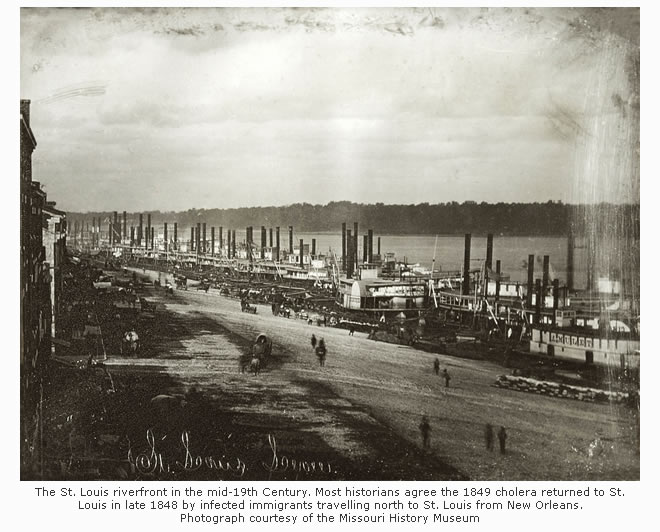

On a cold and dreary evening in late February 1849, a young man with a small journal tucked into the pocket of his overcoat stepped off the steamer Thomas Jefferson and onto the St. Louis riverfront. His name was Joseph J. Mersman, and his story isn’t much different from the thousands of immigrants who poured into St Louis in the years prior to the Civil War. Mersman was of German heritage, born in the Grand Duchy of Oldenburg twenty-five years earlier. He came to America at the age of eight and eventually settled with his family in southwestern Ohio. As a young man, he distinguished himself as a bright, hardworking, and ambitious individual. A whiskey rectifier by trade, he had just concluded a ten-year apprenticeship in Cincinnati. When it ended, he set out to make his own way, and St. Louis is where he’d do it.

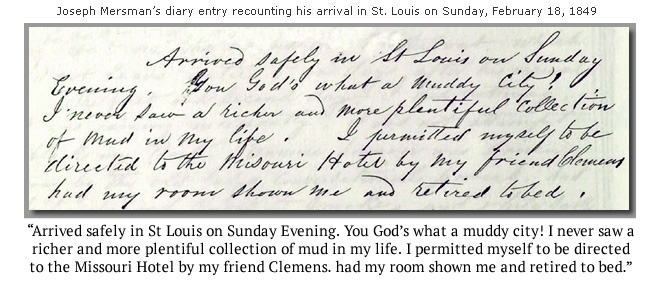

Mersman’s story isn’t exactly unique, but how we know his story is. It’s because of that journal he carried in his pocket. In reading Joseph Mersman’s words, we get his account, in his own handwriting, of a new life in a new city. And the story gets even better because of the month and year he happened to arrive. That’s because in the weeks before Mersman disembarked, another traveler of note arrived in the same way looking to make St. Louis home. The difference is this predecessor didn’t bring cigars, whiskey, and a love for theater like Joseph Mersman did.

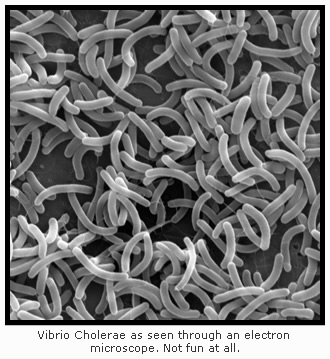

It was Vibrio Cholerae. And it brought death.

Better known simply as “cholera”, no disease gripped people with fear more than the invisible germ that ravaged populations around the world in the 18th and 19th Centuries. St. Louis was no exception. In the fall of 1832, the city’s first major outbreak of cholera killed hundreds at a time when the population barely exceeded 6,000. Just seventeen years later, the number of people calling St. Louis home had soared past 70,000. And when Joseph Mersman became one of them in 1849, St. Louis was on the precipice of a truly gruesome summer. By August 1, just six months later, ten percent of the city’s population would be dead.

The exact number of people killed in the 1849 cholera outbreak is actually unknown. Dr. William McPheeters, a prominent physician in St. Louis at the time, tallied 4,557 in an article published in the wake of the outbreak. However, most historians agree the number is much higher, closer to seven or eight thousand. The disease killed so quickly and on such a massive scale, many deaths weren’t (or simply couldn’t be) reported. Hundreds of victims that succumbed to the disease were simply buried, thrown in the river, or dumped on carts that traveled the streets at night picking up bodies. Regardless of the final number, cholera’s resurgence in 1849 killed unlike anything in the city’s history.

Upon his own arrival, Mersman writes in his journal about how muddy St. Louis is. It’s actually quite an understatement. Familiar with life in an urban jungle (he came from Cincinnati, which was much larger than St. Louis in 1849), Mersman was simply used to it. But someone visiting from the 21st century would be horrified by the sanitary conditions of St. Louis in 1849. The city was congested, it reeked, it was polluted, and it was teeming with filth.

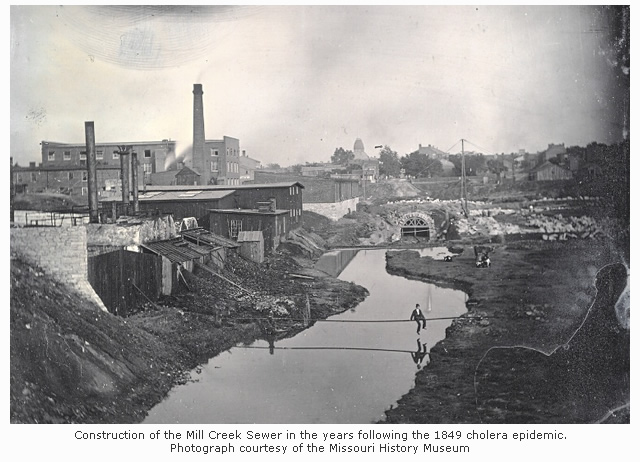

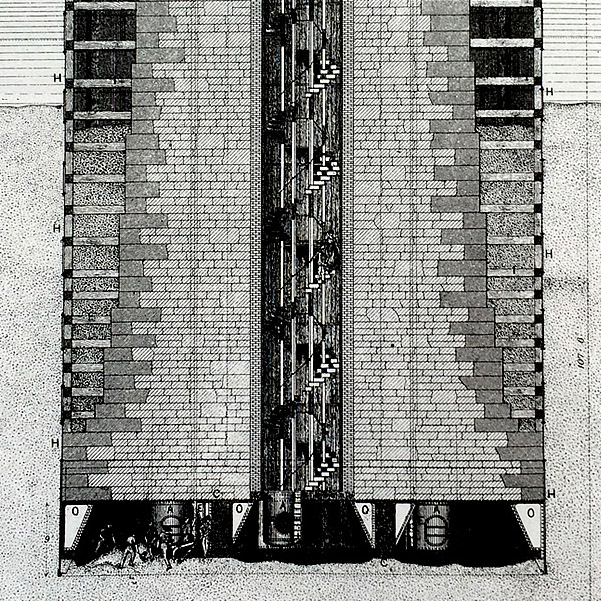

The average St. Louisan living in 1849 inhabited a city that perhaps grew too quickly for its own good. When Joseph Mersman arrived, the city had yet to implement key infrastructure elements. A functioning sewer system is just one example. As a result, the disposal of waste, particularly human waste, was often handled in a primitive way. If not right onto the street, people regularly dumped feces into creeks, ponds, and the Mississippi River. With little knowledge of the danger it introduced, it was also commonplace to find privies and outhouses erected directly next to wells and cisterns.

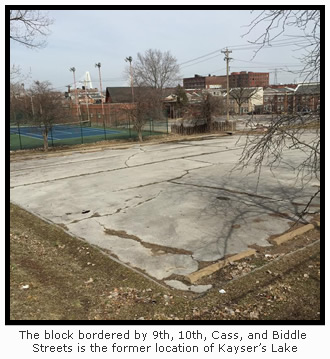

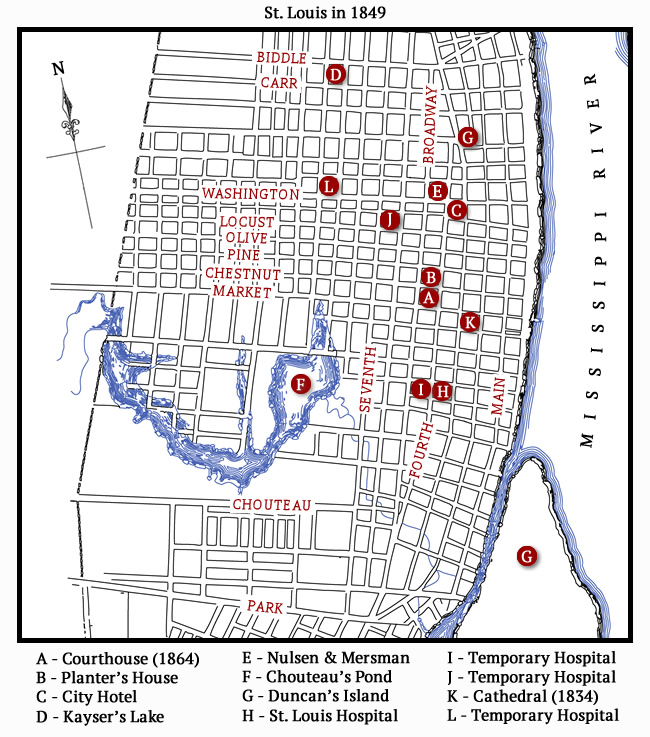

Many St. Louisans realized it was a growing problem and tried to do something about it. In a notable example, an engineer named Henry Kayser suggested using the limestone sinkholes beneath the city as a natural sewer. It worked, but a densely populated city can quickly overwhelm nature. After heavy rains, the sinkholes backed up, forming a block-sized pond of human waste and festering water at the north end of the city. It was dubbed “Kayser’s Lake” by nearby residents disgusted with the result.

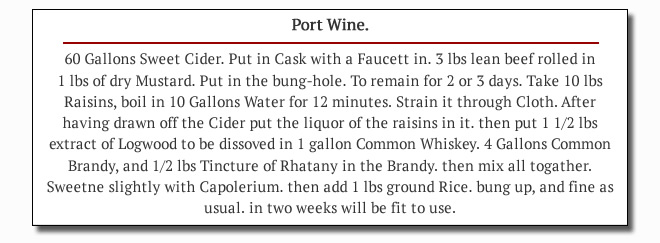

While cholera was beginning to get a head of steam, Joseph Mersman was beginning a new career. He was by trade a whiskey rectifier, a profession that entailed purchasing cheap whiskey made from surplus corn and improving it. This was done by re-distilling it and adding various ingredients to improve the taste. When the process was complete, the improved spirit was sold to hotels, saloons, brothels, and anyone else who would buy it. His partner in trade was a man named John Clemens Nulsen. Both of German heritage, the two men formed a lasting friendship along with a successful business selling whiskey.

While cholera was beginning to get a head of steam, Joseph Mersman was beginning a new career. He was by trade a whiskey rectifier, a profession that entailed purchasing cheap whiskey made from surplus corn and improving it. This was done by re-distilling it and adding various ingredients to improve the taste. When the process was complete, the improved spirit was sold to hotels, saloons, brothels, and anyone else who would buy it. His partner in trade was a man named John Clemens Nulsen. Both of German heritage, the two men formed a lasting friendship along with a successful business selling whiskey.

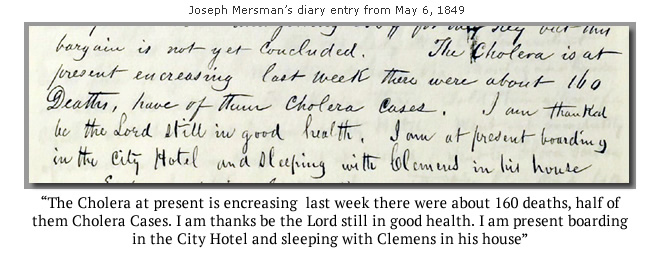

Joseph Mersman knew cholera was on the rise even before he arrived in St. Louis. He notes reports of outbreaks in New Orleans and Vicksburg, which meant cholera was likely working its way up the Mississippi. It was just a matter of time until it reached St. Louis.

Cholera is a deadly disease caused by a microscopic bacterium. Look at Vibrio Cholerae through a microscope and it looks like a curvy little worm. But if a human being ingests about 100 million of them (which a glass of tainted water can provide), death may come within a matter of hours. Cholera does this by rapidly reproducing and clinging to the walls of a human small intestine. An epidemiologist could provide a more scientific explanation, but the quick version is as cholera continues to multiply, the body is essentially tricked into discharging water (mostly through extraordinary bouts of diarrhea). That’s how cholera kills. It dehydrates its victim, and it does it very quickly.

Dr. William McPheeters, the same man who tallied the number of dead when it was over, was also the man to treat the first reported case of the outbreak on January 5, 1849. His patient, a stocky German who had arrived in St. Louis on a steamboat from New Orleans, was described as “Vomiting freely, with frequent and copious discharges from the bowels; at first of slight bilious character, but it soon became pure “rice water.” As the disease progressed, his patient suffered intense abdominal pain and his skin became “of a blue color and very much corrugated.” McPheeter’s first patient died the next morning.

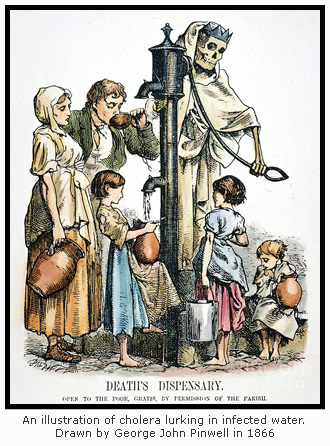

The diarrhea, or “rice water” as Dr. McPheeters referred to it, is one of the primary symptoms of cholera. It consists of evacuated bodily fluids (mostly water) and small bits of intestinal lining (that happen to resemble rice). It’s an unpleasant scenario to consider, but it’s important in the understanding of how cholera spreads from one person to another. In St. Louis and cities around the world, buckets of “rice water” discharged from cholera patients were often poured right into a city’s water supply. When a neighbor came to retrieve a bucket of drinking water for the day, the cholera within was essentially being hand-delivered to its next victim.

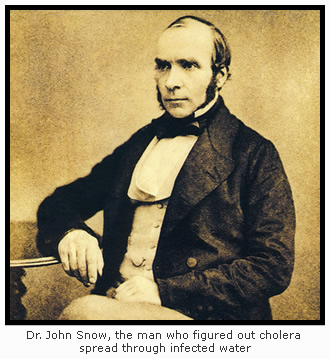

This helps explain why St. Louis became the most deadly American city to be living in during the summer of 1849. In a crowded, polluted, river-dependent city, nobody understood that infected water was spreading cholera. In fact, only one person had started to figure it out, but he lived half a world away. John Snow, a noted physician and scientist in London was piecing together his theory at the same time cholera was closing in on St. Louis. Snow wouldn’t prove his theory until five years later, when he isolated a single water pump in London’s Soho neighborhood as the culprit behind a cholera outbreak that ravaged London in 1854.

But in the mid-19th century, few were willing to accept such a theory. Nearly everyone believed they already had cholera figured out. While many chalked it up as a punishment from God, most people believed that diseases such as cholera, the plague, and even chlamydia were spread through foul air, specifically by the noxious fumes generated by rotting organic matter. This is the miasma theory, and it was widely endorsed in the mid-19th century. It’s advocates included John Snow’s colleague William Farr, Florence Nightingale, and St. Louis’s own Dr. William McPheeters, who wrote of the 1849 outbreak:

As detailed earlier, St. Louis had more than its fair share of rotting organic matter. And in neighborhoods packed with slaughterhouses, poorly built graveyards, animal pens, tenements, and tanneries, the stench was often overpowering. With gagging at the smell of rotting flesh and fecal matter a natural reaction in every living human, it’s not a stretch to believe that people once believed noxious vapors played a role in making people sick.

As 1849 moved into spring, the spread of cholera began to pick up steam in St. Louis. By the end of May, cholera was killing up to eighty people a day. As a result, it’s estimated that up to 20,000 people fled the city (some sources estimate up to half of the population picked up and left). Around this time the city started to take action. Arsenal Island, located south of the city, was turned into a quarantine zone. All boats traveling north were required to stop and be inspected. Anyone on board showing symptoms of cholera was forced to remain on the island until dead or until symptoms disappeared.

As 1849 moved into spring, the spread of cholera began to pick up steam in St. Louis. By the end of May, cholera was killing up to eighty people a day. As a result, it’s estimated that up to 20,000 people fled the city (some sources estimate up to half of the population picked up and left). Around this time the city started to take action. Arsenal Island, located south of the city, was turned into a quarantine zone. All boats traveling north were required to stop and be inspected. Anyone on board showing symptoms of cholera was forced to remain on the island until dead or until symptoms disappeared.

Joseph Mersman remained in the city to keep his new business running, but wrote on May 13th that the “City looks like a desert Compared to its usual appearance”. Regardless, Mersman did his best to maintain a normal life. He continued to focus on work, visit saloons with friends, and attend theater productions.

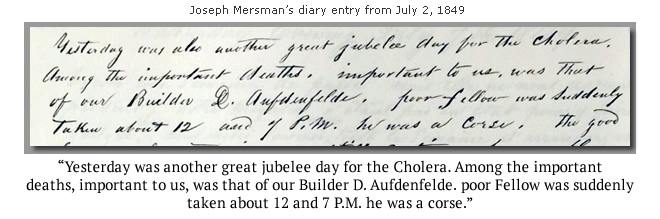

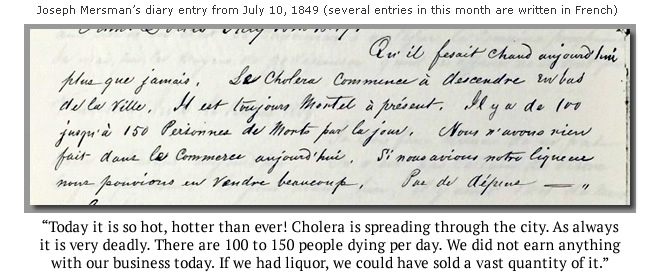

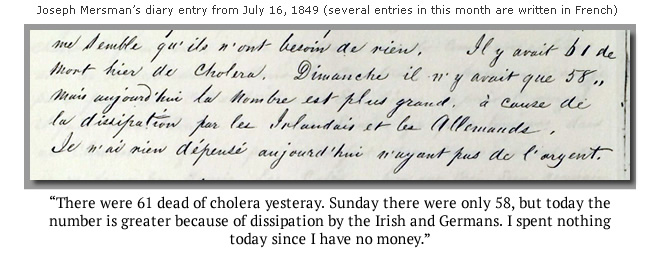

But things would go from bad to worse. On May 17, a fire broke out on the riverfront destroying much of the downtown business district. Raging for nearly twelve hours, the blaze destroyed over 400 buildings. Remarkably, many St. Louisans welcomed the fire, hoping it would also burn away the contagion spreading through the city. Then cholera hit close to home when Mersman’s own building contractor fell to the disease. In the wake of this, Mersman becomes less inclined to wander about in his new city. He writes “one cannot be certain of staying alive for another day” and makes a point to complete his work early each day and remain close to home. He uses the time to study languages, which he practices by writing many of his journal entries en français.

June and July brought the worst of it. With hundreds dying everyday, terror gripped the city. Tired of waiting for the city to act, the people of St. Louis took matters into their own hands. After several prominent citizens angrily confronted city officials, a Committee of Public Health was formed, consisting of the mayor (the only city official allowed to join) and various members of the community. Completely ignorant of cholera’s methods, the committee held fast to the theory that miasma was behind it all. In short order, several extraordinary city regulations were implemented. However, none of them addressed the city’s contaminated water supply.

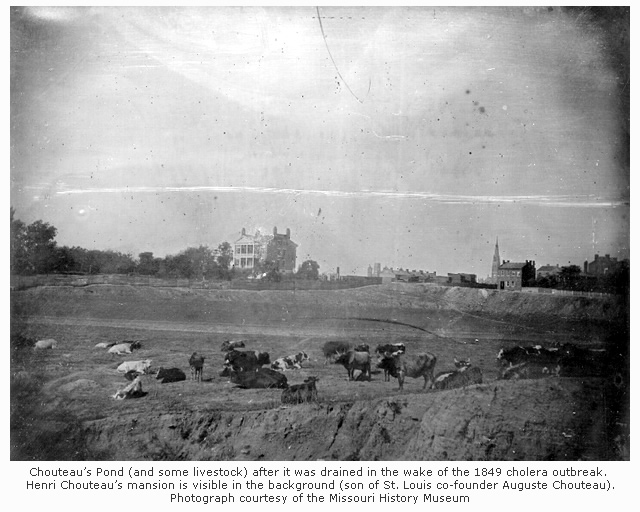

Keeping hogs in the city was forbidden until the outbreak was over. Scavenger carts were ordered to make rounds in city neighborhoods, picking up garbage, dead animals, and sewage (with the contents frequently being dumped into the river or Chouteau’s Pond). Fines were levied on citizens who didn’t keep their property clean and free of filth. People were advised to burn sulphur and coal in order to rid the air of disease. Temporary hospitals were established around the city, with a multitude of doctors and collection vehicles assigned to each. Fish, veal, and pork were banned, despite doctors insisting on a strict diet of nothing but meat. Long suspected of spreading cholera, vegetables were banned from being sold in city markets. Since many believed the disease originated in poor neighborhoods crowded with German and Irish immigrants, some concluded (including the previously mentioned Dr. William McPheeters) that even sauerkraut and cabbage had something to do with cholera’s wrath. And in a city that would become famous for making it, even beer was banned in St. Louis during the summer months of 1849.

Remarkably, perhaps by an overall improvement in city sanitary conditions, or that death and flight left fewer people in St. Louis for cholera to infect, or maybe Vibrio Cholerae had simply run its course, the number of reported cases began to drop significantly in the final days of July 1849. The city declared it over on August 1, and by mid-August, Dr. McPheeters tallied deaths by the week instead of by the day.

Remarkably, perhaps by an overall improvement in city sanitary conditions, or that death and flight left fewer people in St. Louis for cholera to infect, or maybe Vibrio Cholerae had simply run its course, the number of reported cases began to drop significantly in the final days of July 1849. The city declared it over on August 1, and by mid-August, Dr. McPheeters tallied deaths by the week instead of by the day.

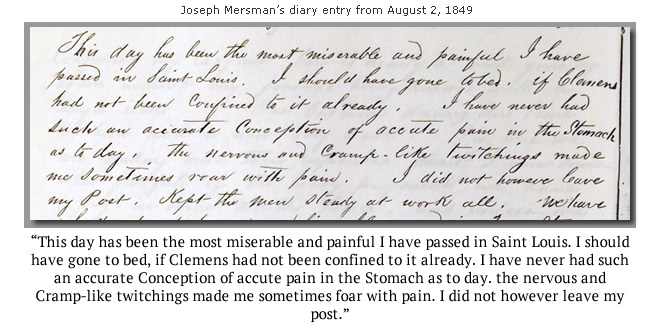

It didn’t go out without a fight. It had one more go at the man who had been writing about it all summer. On August 1, Joseph Mersman must have agonized as he witnessed his business partner Clemens Nulsen become afflicted and suffer through the symptoms of cholera. Knowing his close friend could be dead within hours, Mersman tried to ease his mind by concentrating on business matters. Then, on the very next day, Joseph Mersman felt the sharp pinch of severe abdominal pain. Cholera had finally come for him too.

Remarkably, Joseph Mersman and John Clemens Nulsen both survived. And in the wake of it, the two men would have many more reasons to celebrate. Along with a successful business, the two men became brothers-in-law when Mersman married Claudine Creuzbauer in 1851 (Nulsen had married Claudine’s sister Albertine in 1848). John and Claudia had eight children together, which must explain why his daily musings in a journal became few and far between in the years after their marriage. With fortune at hand, the family moved into a stately home in the Lafayette Square neighborhood. Leaving a healthy estate behind (that his children grappled over), Joseph John Mersman died on March 26, 1892.

As for St. Louis, The 1849 cholera epidemic had a lasting impact on the city. Most importantly, the death toll of nearly 10% shattered hundreds of families across the city. It was impossible for any one individual to avoid some level of tragedy. But as families mourned loved ones lost, St. Louis quickly went to work making the city safer and more livable. Chouteau’s Pond and Kayser’s Lake were drained, sewer systems were built, sanitation improved, and rural cemeteries such as Bellefontaine and Calvary were founded outside of city limits. Many who fled the city to escape cholera stayed away, leading to the growth of towns and communities beyond city limits. It also led to the development of new areas within the city, luring wealthy citizens such as Robert and Virginia Campbell (who lost their oldest son to the epidemic) and Henry Shaw to spend more time away from a dirty and congested riverfront.

And finally, cholera wasn’t done either. It reared its head again in 1853 and 1873, but each time on a much smaller scale. And despite John Snow’s efforts in London, western civilization didn’t really get a handle on the little germ until 1884 when the German microbiologist Robert Koch finally put the miasma theory to rest. Koch confirmed and publicized the findings of Filippo Paccini, an Italian scientist who’s isolation of Vibrio Cholerae was disregarded thirty years earlier.

I’ve rarely been more excited in my few years writing Distilled History than the moment I learned about Joseph Mersman’s diary.

I’ve struggled a bit recently finding really good drink connections (James Eads presented a challenge), but it’s like Joseph Mersman simply fell into my lap. Not only did he provide a fascinating perspective of St. Louis during its darkest hours, he was a whiskey man.

Upon his arrival in St. Louis, Mersman writes about getting to know the city, and much of this is done by attending theater and drinking in saloons. He never mentions it by name, but it’s very likely he had a drink or two at the Planter’s House Hotel, located just down the street from the whiskey rectification business he operated with John Clemens Nulsen. It’s also possible he was also served by the cocktail icon Jerry Thomas, who tended bar at the Planter’s House during Mersman’s early days in St. Louis.

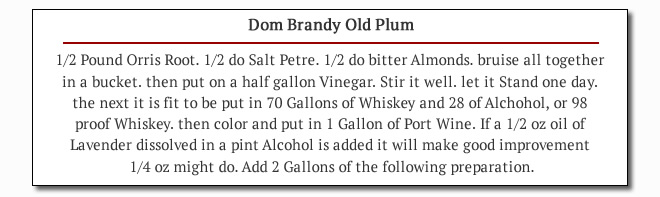

Anyway, what’s even more exciting is Joseph Mersman scrawled out many of his own whiskey rectification recipes in the same journal that detailed cholera. If I had more time (and 70 gallons of whiskey on hand), it would be a fun project to not only fully decipher his recipe for “Dom Brandy Old Plum”, but scale down the ingredients and try it myself.

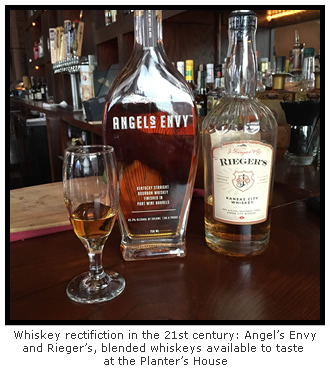

But until then, I knew the guy I had to talk to about whiskey rectification in the 21st century. Ted Kilgore, the mad cocktail genius at the (new) Planter’s House, needed about three seconds to understand what I was up to. After watching him run off, and getting a hug from his lovely wife (this blog has its perks), Ted returned and presented me with two blended whiskeys to try. Of the two I picked Angel’s Envy, a blended Kentucky straight bourbon aged in port wine barrels. Very smooth and delicious, I noted raisins in the aroma.

Port wine and raisins. Joseph Mersman would certainly approve. The same ingredients exist in one hell of a recipe that probably helped him get through the terrifying days of one hell of a summer.

Key sources and additional reading:

-

Joseph J. Mersman Diary – Missouri Historical Society

- “A Summer of Terror: Cholera in St. Louis, 1849” by Linda A. Fisher Missouri Historical Review Vol. 15 (April 2005)

-

“History of Epidemic Cholera in St. Louis in 1849” by William M. McPheeters St. Louis Medical and Surgical Journal 7 (March 1850)

-

“Cholera Epidemics in St. Louis” Missouri Historical Society – Glimpses of the Past 3 (March 1936)

-

“The St. Louis Cholera Epidemic of 1849” by Patrick E. McLear Missouri Historical Review 63 (January 1869)

- The Whiskey Merchant’s Diary: An Urban Life in the Emerging Midwest edited by Linda A. Fisher

- The Ghost Map: The Story of London’s Most Terrifying Epidemic and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World by Steven Johnson

- Lion of the Valley by James Primm

This was a fascinating article. Great work! I’ve been fascinated by cholera and how many of our most beautiful cemeteries were developed because of it. It must have been an exciting and scary time. Did cholera spread through other parts of Missouri in the same year? I wondered about Lexington, which was a much larger city just before St. Louis exploded in population.

I’m not sure about Lexington specifically, but the outbreak hit just about everywhere (along with larger cities to the east such as Philly, Boston, Cincinnati, etc). Check out the sources at the bottom of the post. One of them was about the outbreak in Missouri as a whole, but I focused on the St. Louis information from it.Thanks for the nice words!

Great work, Cameron. Muchas Gracias.

Pickles were also blamed for cholera.

Ha! That’s right. I have a friend with a cat named Pickles. She won’t like this news.

The cholera outbreak of 1849 sounds positively horrifying! But it’s so fascinating to learn how it impacted our city, both in its death toll and in the way it was the impetus for so many improvements in our city. I’ll drink to that!

Another great article, Cameron! Keep drinking and writing!

Thanks so much! Glad you dig it.

Great article…….history of St. Louis

As always, excellent post. I always find myself poking around google maps to see the places you mention.

Geeky addition: This is also what inspired the City to start keeping track of deaths in 1850.

I was both horrified and mesmerized with this story — outstanding research and very well done!

Wonderful reading by an excellent writer! Thank you so much for this look into 19th-century Saint Louis.

Thanks for reading! This was a fun one to write.

Great article! Loved reading it and learning the history. Thank you.

Lead Pipes in Iraq ElitePipe Factory is recognized as a trusted provider of lead pipes in Iraq. Despite the decline in use of lead pipes in modern applications due to health concerns, ElitePipe Factory maintains a legacy of supplying high-quality lead pipes for specific applications where they are still needed. Our commitment to reliability and excellence ensures that we offer products that meet the highest standards of performance. For information on our lead pipes and their applications, visit our website at ElitePipe Iraq.