It continues to be my favorite “thing” in St. Louis history.

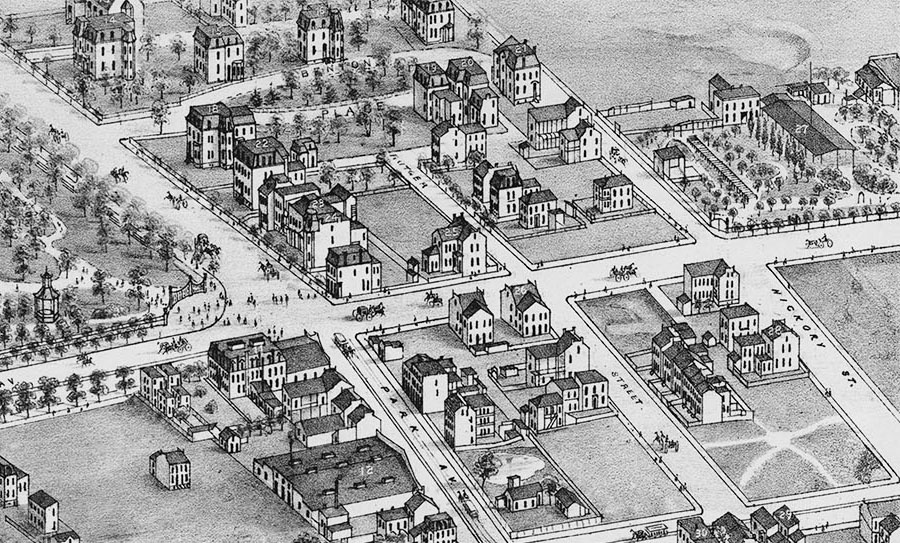

A map often referred to simply as “Compton and Dry” after the man who published it (Richard Compton) and the guy who drew it (Camille Dry), the map’s official name is Pictorial St. Louis, the Great Metropolis of the Mississippi valley; A Topographical Survey Drawn in Perspective A.D. 1875. It’s a map unlike any other, and I am not kidding when I say I look at it and think about it every single day.

That’s because it’s my desktop wallpaper, it’s mounted on 110 4×6 boards in my living room, and a giant version of David Rumsey’s composite is mounted on the wall of my office. When I think about something from St. Louis history (which is often), I always think to myself “I wonder if that’s on Compton and Dry?” The map has been featured in several Distilled History posts, including one of the first in 2012, my efforts to find where every St. Louis brewery stood in 1875 (which was too big of a task for just one post), and dozens of others that reference it or use images from it.

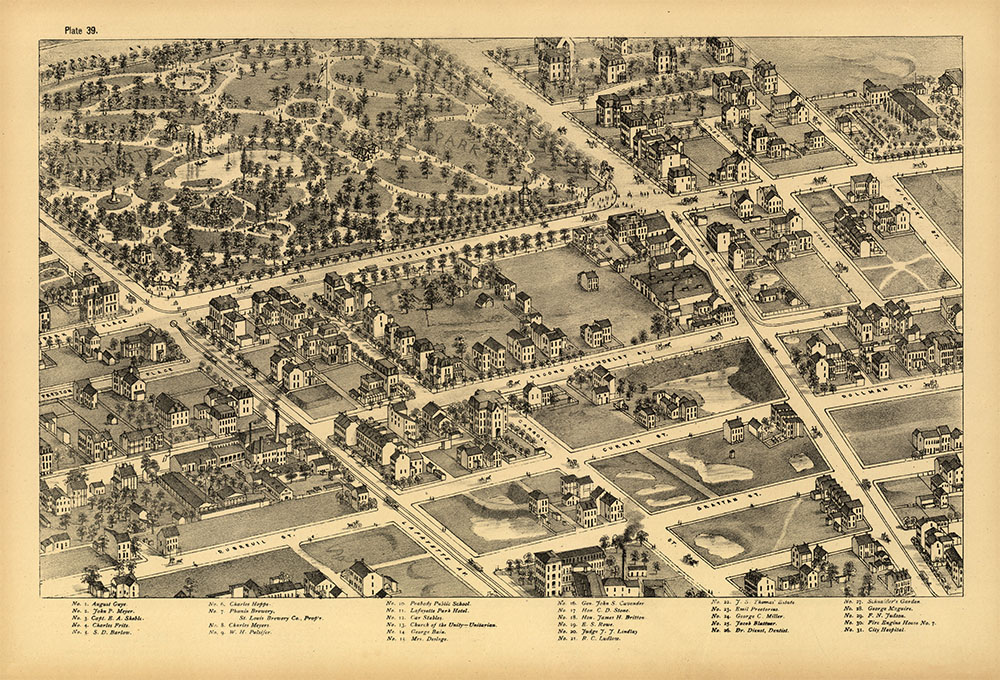

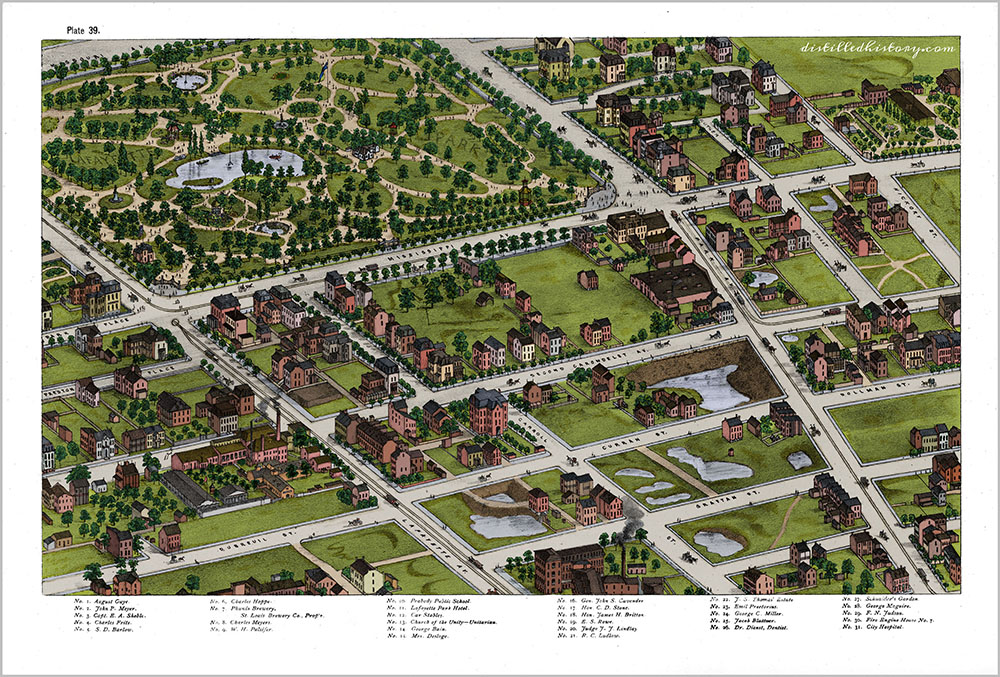

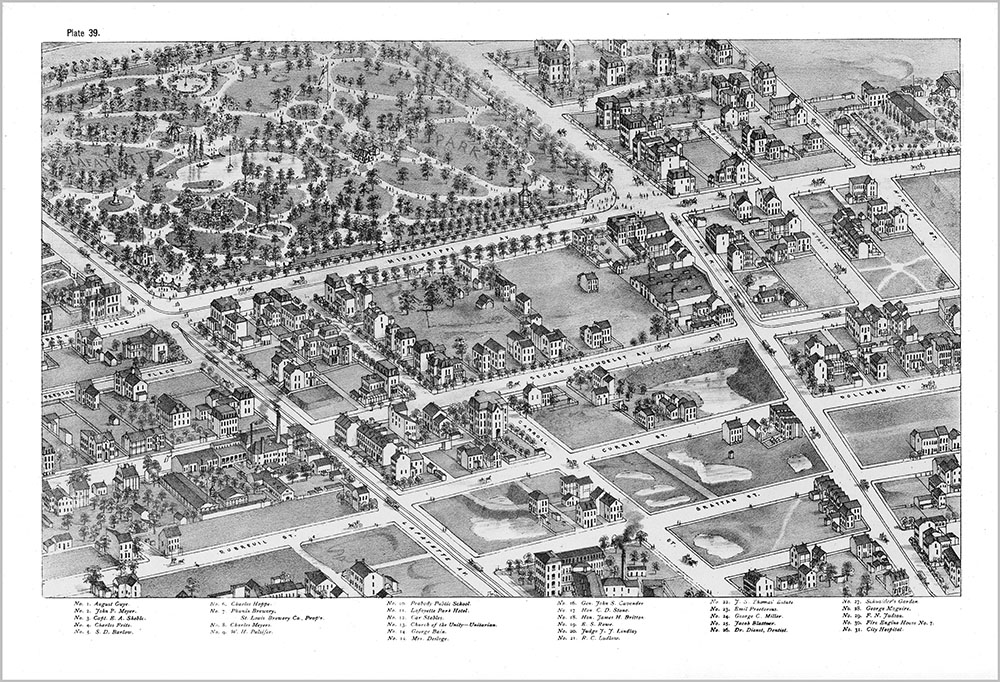

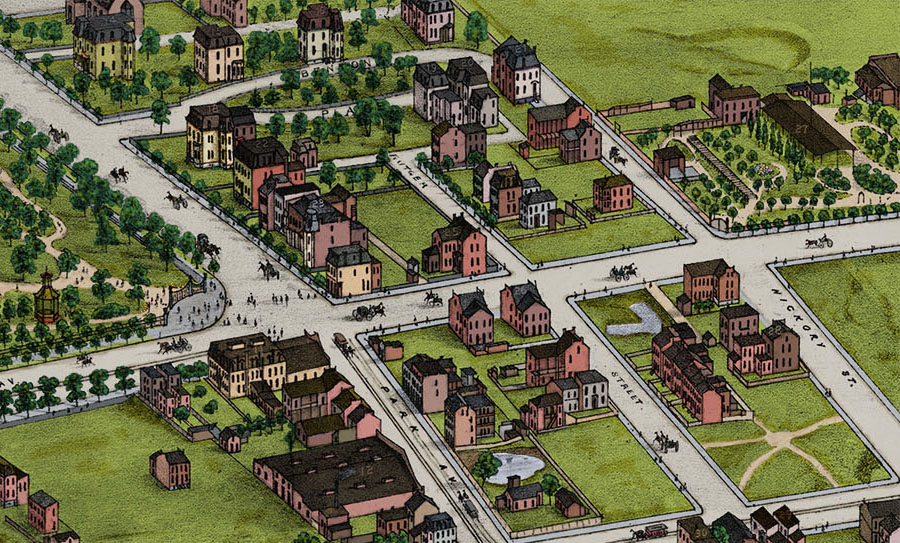

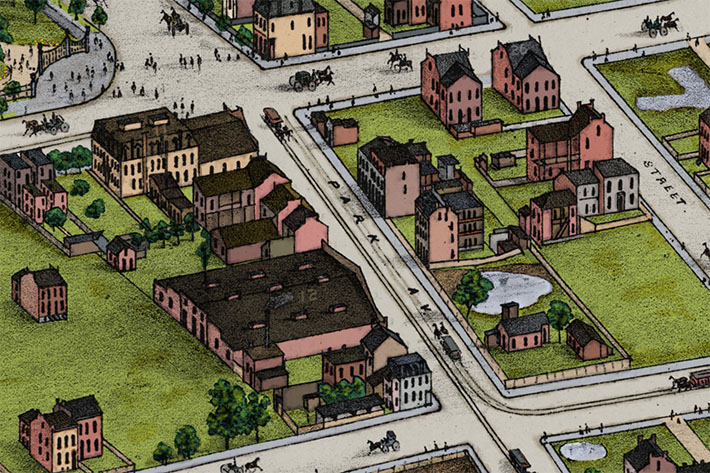

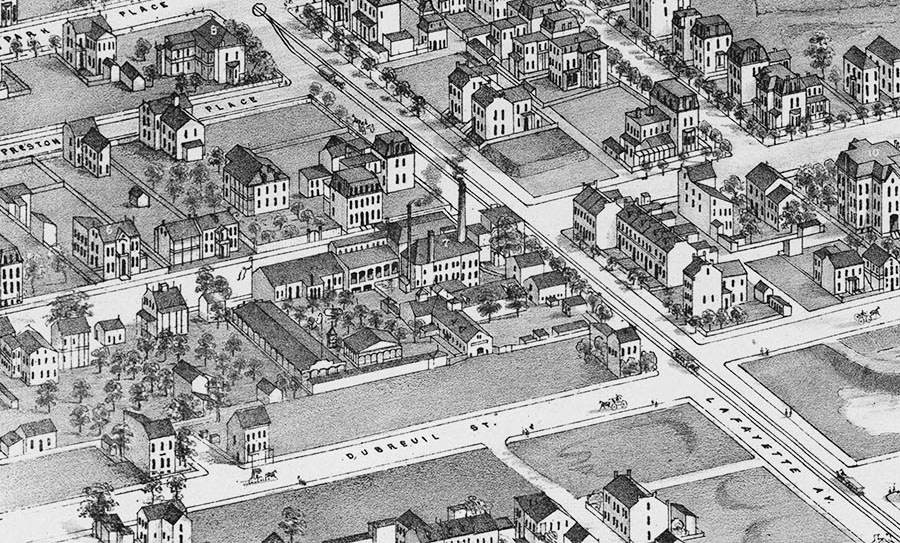

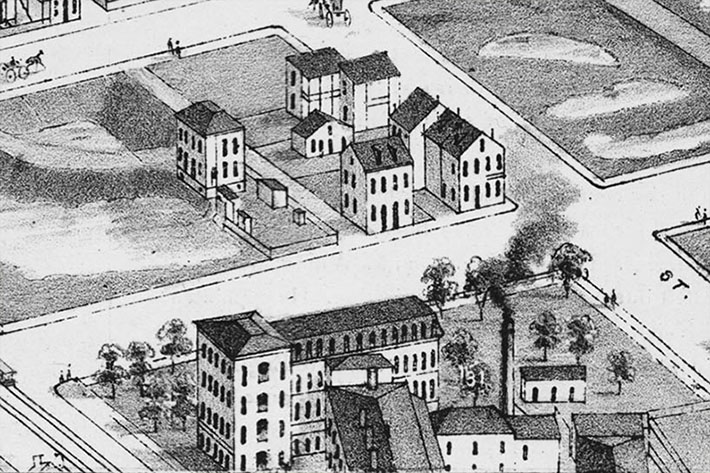

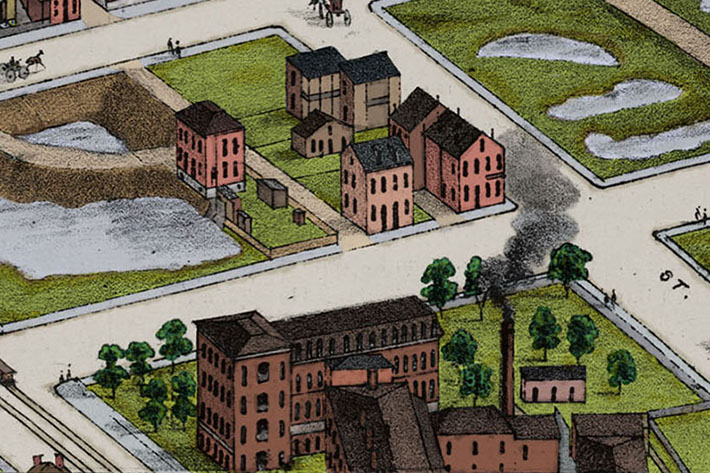

But my deepest dive into Compton and Dry happened in 2015, when I had the loony idea to color the entire thing. Yup, I once had grand plans to create a full-color version of every one of Compton and Dry’s 110 plates, but I was quickly humbled. Read the original post to learn more, but the quick explanation is that the roofs got me. I’m glad I did it, but the densely packed plate 42 was a beast. After I stuck a big print of it on my (other) office wall, I took a deep breath and moved on to other time killers.

But a year or two later, I came back around to coloring another plate. There’s a reason adult coloring books are a thing, and I found coloring trees and mansard roofs in 1875 St. Louis to be a great stress reliever. I also love doing creative stuff in Photoshop (I used a digital pen and tablet to color plate 42), and after (finally) upgrading to Adobe’s latest release, I went looking for another one of Compton and Dry’s plates to add a bit of color to.

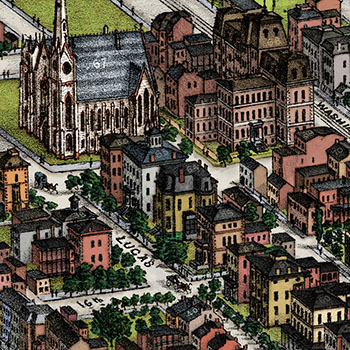

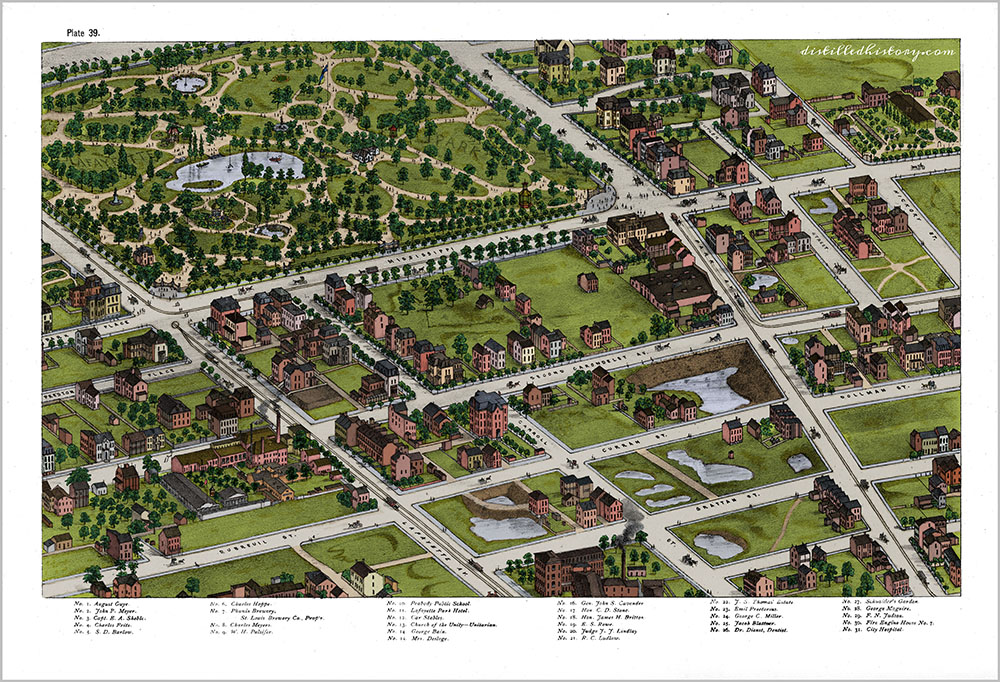

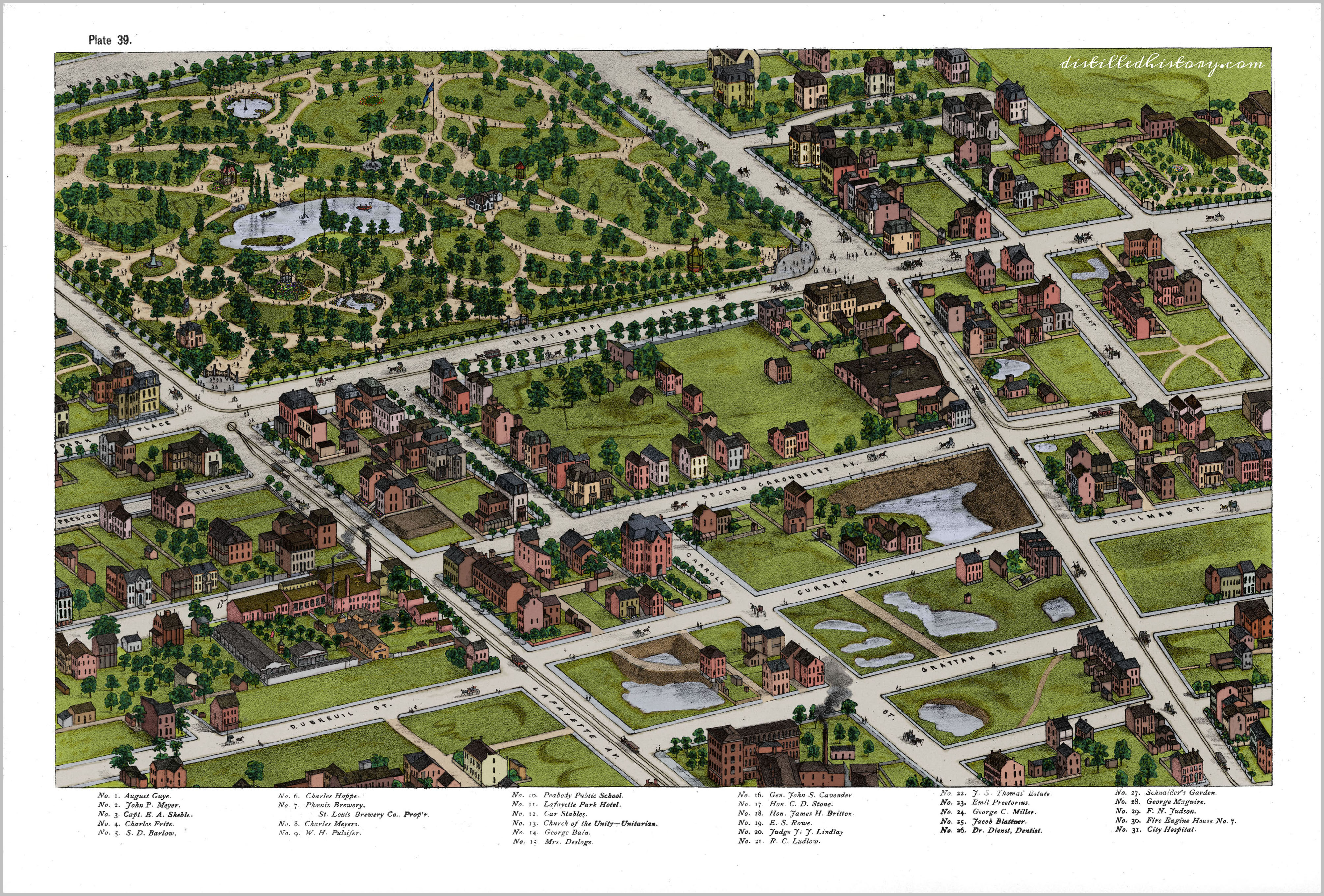

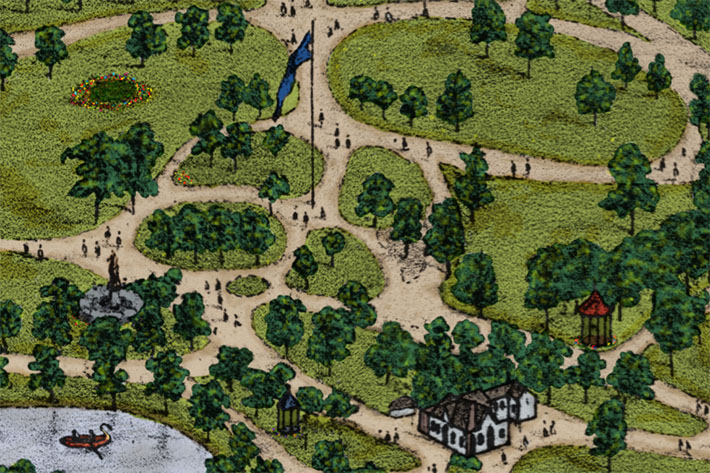

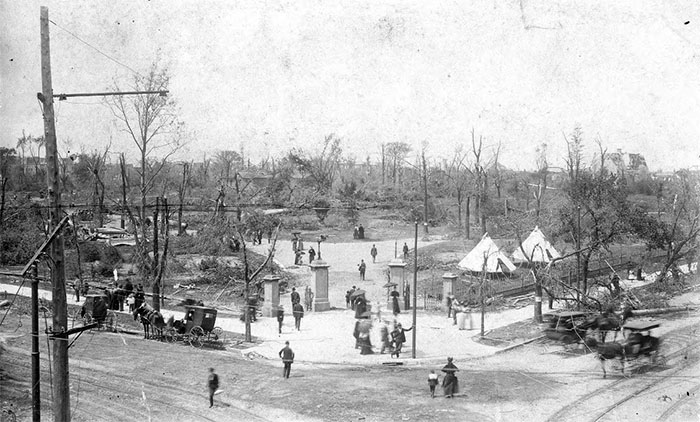

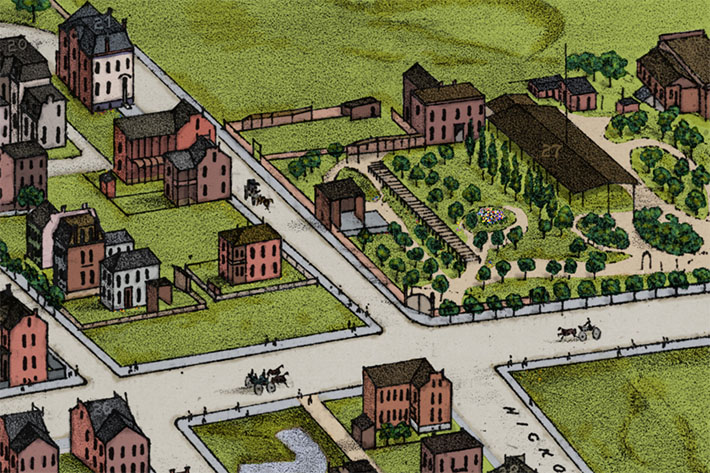

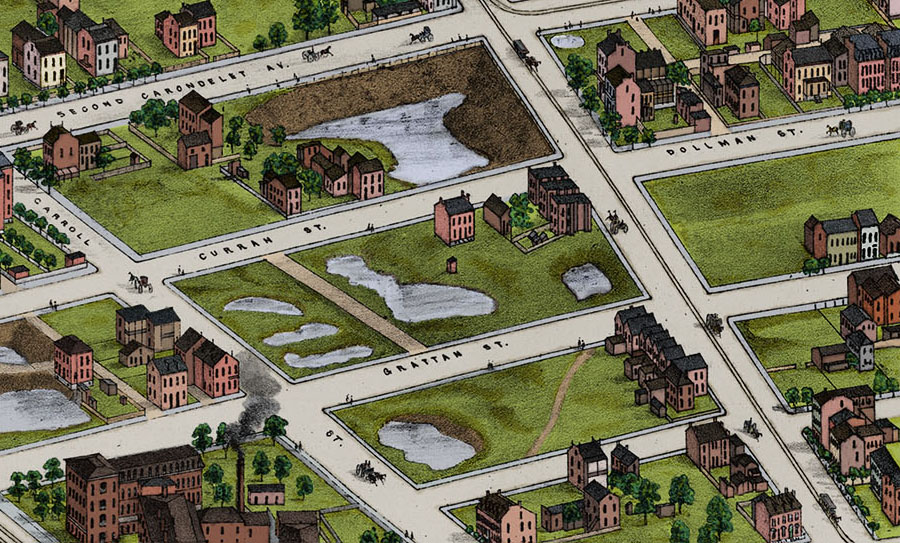

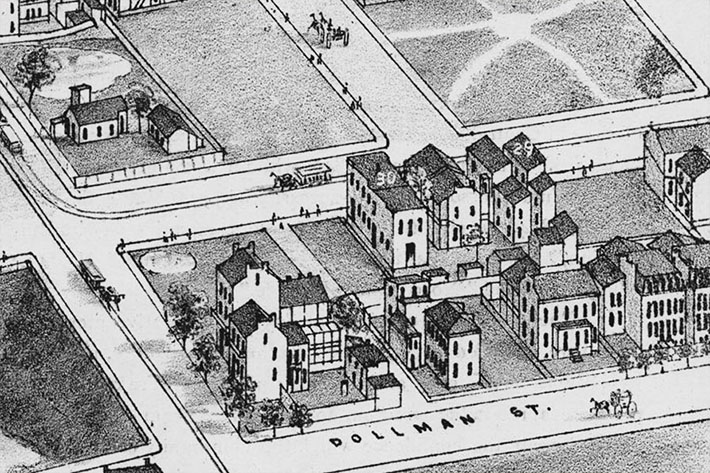

Seeking something away from downtown St. Louis, I quickly selected plate 39. It’s a bit more spread out (fewer roofs), it has a brewery (yes!), and it’s packed with good history. Plate 39 is all Lafayette Square, a neighborhood that has received plenty of attention in this blog, notably with posts about Schnaider’s Beer Garden and the tornado that ripped it apart in 1896. And unlike plate 42, which looks much different from it did in 1875 (only four structures drawn on the plate still remain today), plate 39 is filled with stuff that’s still here. The most significant being the neighborhood’s anchor, Lafayette Park.

Seeking something away from downtown St. Louis, I quickly selected plate 39. It’s a bit more spread out (fewer roofs), it has a brewery (yes!), and it’s packed with good history. Plate 39 is all Lafayette Square, a neighborhood that has received plenty of attention in this blog, notably with posts about Schnaider’s Beer Garden and the tornado that ripped it apart in 1896. And unlike plate 42, which looks much different from it did in 1875 (only four structures drawn on the plate still remain today), plate 39 is filled with stuff that’s still here. The most significant being the neighborhood’s anchor, Lafayette Park.

But before I get to that, I should mention that Lafayette Square also appears on other (currently un-colored) plates. Plate 40 has the northern section, plate 55 contains what lies west of Missouri Avenue, and plate 58 shows the area south of the park (including traces of one of the old Civil War forts). I may get to coloring those someday, but don’t hold your breath. If I have another plate in me, I’ll probably look to the northern half of Compton and Dry’s map.

Anyway, here’s my version of Compton & Dry’s Plate 39 with a bit of color thrown in.

The Lafayette Square neighborhood grew from the park that was first established in 1836. According the memoirs of John F. Darby, St. Louis’s mayor at that time, the selection of the park’s location can be traced back to an exact day: March 7, 1836. Darby writes that on that day, he and a city alderman named Thornton Grimsley rode on horseback to an undeveloped area west of the city known as the St. Louis commons. Colonel Grimsley, A military man and notable saddlemaker in St. Louis, had advocated using the area as a public space and military parade ground. A proposal derided by many due to its distance from the city, the area thus became known as “Grimsley’s Folly”. But Mayor Darby, who opposed other proposals to sell the commons, agreed that a growing St. Louis needed a park.

Before/After Image Slider – Move (hover) the mouse left and right to view before and after versions. (Update: This plugin may not play nicely on mobile devices.)

Image Loupe – Drag the mouse pointer to zoom in parts of the final image.

After Darby and Grimsley plotted out where the park should be, a city ordinance was introduced and passed just two weeks later. The ordinance called for the construction of two new avenues each 120 feet wide. Each avenue would extend from Park and Lafayette Avenues, with the eastern one named “Mississippi” and the western one named “Missouri”. The 30-acre square bounded and formed by the four roads was then reserved as a public square.

Suddenly, St. Louis had its first public park. Initially called the “Public Parade Ground” (thanks to Grimsley), it was later renamed after the Marquis de Lafayette and dedicated as the city’s first park in 1851. Today, many historians believe Lafayette Park was also the first public park established west of the Mississippi River.

The park would become the city’s most popular recreation spot, but it didn’t happen overnight. According to an article written by Lafayette Square historian Mike Jones, the park may have resembled more of a beer garden than a flower garden in its early years. To shake things up, in 1864 park trustees replaced the park’s superintendent with notable landscape architect Maxmilian Kern. Over the next five years, Kern transformed the 30-acre square into a botanical marvel. Along with trees, shrubbery, and floral displays, the park featured a lake with swan boats and a bandstand. Other amenities included a rock garden, pavilions, and gravelled walkways that made the park a haven for strollers and picnickers. At the same time, the neighborhood around the park developed as wealthy St. Louisans moved in and began building some of the most magnificent residences in the city.

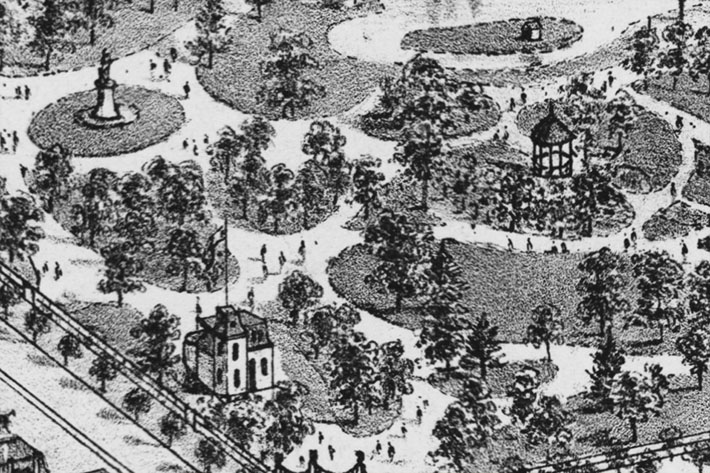

A Closer Look: Upper-Left

Nearly all of Lafayette Park is visible in the upper-left section plate 39. Although many of the park structures had to be rebuilt after the 1896 tornado, plate 39 contains several that still exist. Built in 1867 as a police station, the Park House located at the bottom-left is still there. A bronze statue of Thomas Hart Benton, the former Missouri Senator and St. Louis advocate, has stood tall (and looking west) since 1868. Celebrating its 150th anniversary in 2018, statue was the first public monument in the United States created by a woman (Harriet Hosmer) and the first one west of the Mississippi River. When it was dedicated on March 27, 1868, more than 40,000 gathered in the park to witness the unveiling.

Other notable park features seen on plate 39 that still exist today include the statue of George Washington near the Park House (1869), the park’s iron fence and stone gates (1869), and the rocky grotto (1866).

The Park House

This close-up provides a better look at the Park House, the statue of George Washington, and a pavilion that stood where the Elizabeth Cook Pavilion now stands.

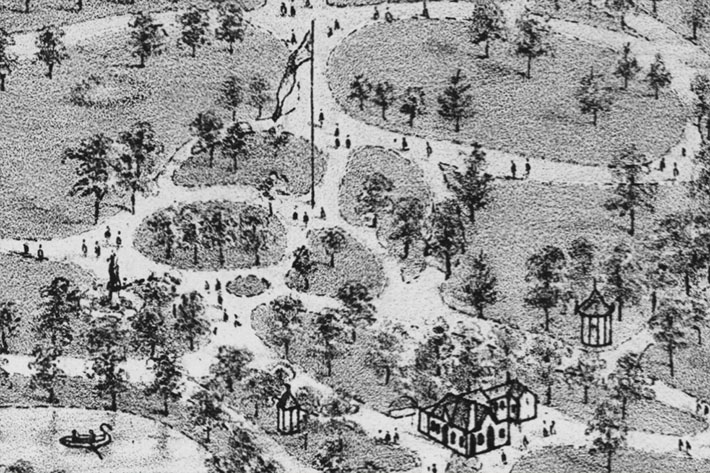

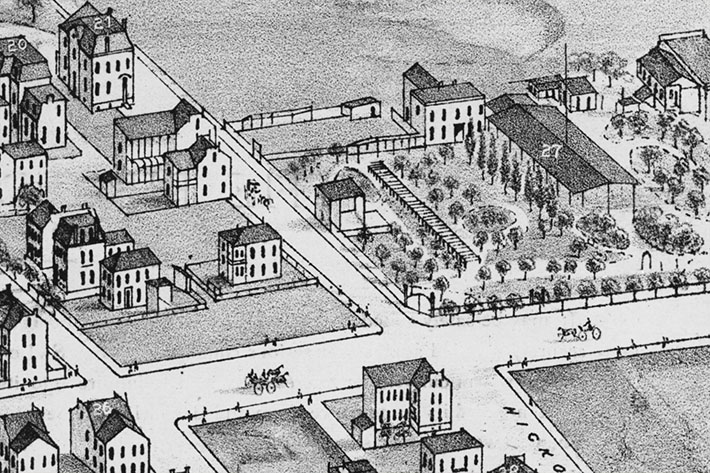

The Flagpole

Along with a few other structures no longer standing (again, the tornado), one throwback to Lafayette Park’s original purpose is the large flagpole that Camille Dry drew to the north of the main lake. It marks the parade ground where Colonel Grimsley marched his “home guard” in the early years of the park’s existence. Lafayette Park was also used as a camp for Union soldiers during the Civil War. The Thomas Hart Benton statue stands south of the flagpole, and the superintendent’s cabin sits just to the east (which no longer exists).

A Closer Look: Upper Right

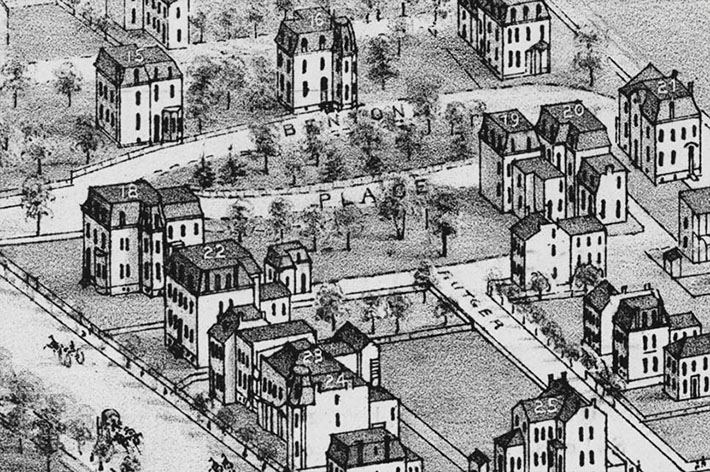

Along with several notable structures, the upper-right section of plate 39 contains the southeast entrance to the park. Benton Place, the streetcar stables, and Schnaider’s Beer Garden are also visible in this section.

Benton Place

A street with enough history to fill an entire Distilled History post, the oval-shaped Benton Place was of the nation’s first private streets. Plotted around a grove of trees by Julius Pitzman in 1866 for Montgomery Blair (Abraham Lincoln’s Postmaster General), Benton Place was home to several prominent St. Louisans. One of Blair’s mansion’s, 5 Benton Place (labeled #15 on the map), still stands today. In 1875, it was the home of Cynthia Desloge, a woman of great wealth and legendary socialite of the time.

Next door at 21 Benton Place (labeled #16) lived John Cavender, a man who made his fortune in insurance. 21 Benton Place is also notable for the man who bought the home in 1949 and completely restored it. John Albury Bryan, an architect and pioneer of historic preservation in St. Louis, is a major reason Lafayette Square is still here today. When many of the grand residences of Lafayette Square fell into disrepair in the 1930’s, many called for the neighborhood to be leveled and built anew. At a time when it wasn’t fashionable to do so, Bryan relentlessly (and successfully) fought for the Lafayette Square’s preservation and restoration. His other projects included Henry Shaw’s Tower Grove House and the Campbell House.

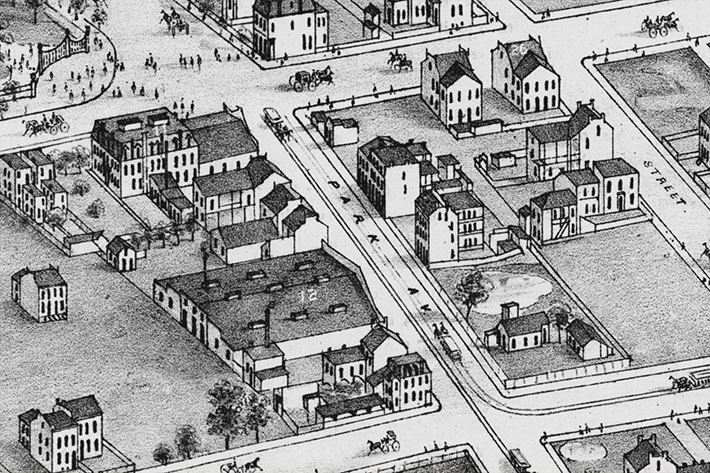

Streetcar Stables

Located east of Lafayette Park on Park Avenue, the car stables for the St. Louis’s horse-drawn streetcar system can be found. According to Andrew Wanko at the Missouri History Museum (who graciously provided much of is own research on plate 39), this stable held the cars that would travel down Chouteau Avenue and head into the city after turning left on 4th Street. It’s likely that many residents of the the neighborhood weren’t thrilled about the stable’s location within their exclusive neighborhood.

Schnaider’s Beer Garden

Last but certainly not least, I’ll never miss an opportunity to give Schnaider’s Beer Garden a little love. A garden that could hold thousands of thirsty beer drinkers at once, it’s another reminder that Compton and Dry didn’t draw many people wandering around. They also didn’t draw much dirt. I thought about creating a more realistic area of plate 39, filled with horse manure, sludge, and whatever else was really there. But Lafayette Square was probably tidier than most of St. Louis in 1875, so I’ll save that for the next plate.

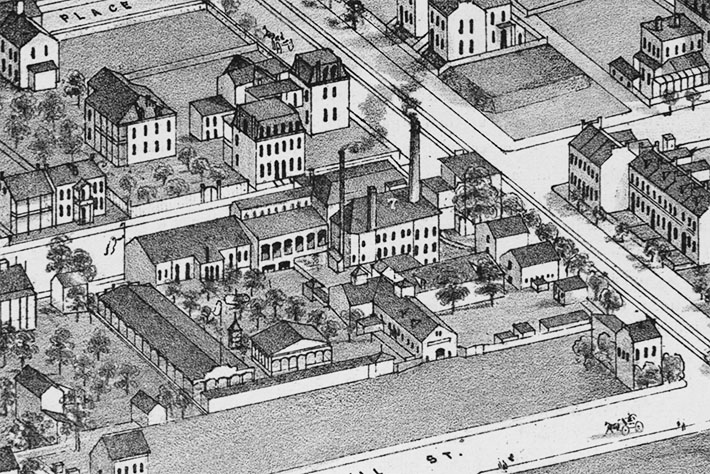

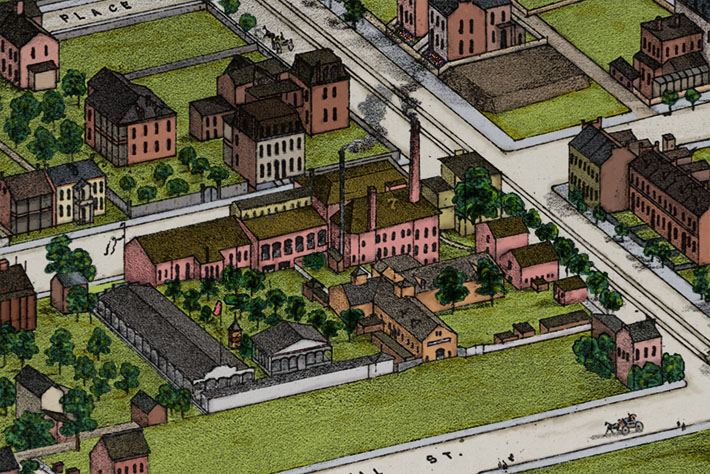

A Closer Look: Lower-Left

The prominent structure (well, in my opinion) in the lower left section of the plate is the Phoenix Brewery (labeled #7), which once stood where the on-ramps to Highways 55 and 44 from Lafayette Avenue now sit. Built in 1841, the Phoenix Brewery was one of the largest breweries in St. Louis in its early years, but it was likely closed in 1875 due to financial reasons. The complex later became home to a branch of one of the city’s prominent brewing families. In 1883, Anton Griesedieck and his sons bought the plant and began producing Pearl Beer.

Kennett Place

Number 5 on plate 39 marks the home of Stephen Barlow. A member of Lafayette Park’s original board of commissioners, Barlow was responsible for the development of Kennett Place, the first major development on the east side of Lafayette Square.

A Closer Look: Lower-Right

City Hospital

Labeled #31, the City Hospital can be seen at the lower-left of this section. Originally built in 1846, the version seen on Compton and Dry’s plate 39 replaced the structure that burned in an 1856 fire. This one was then destroyed by the 1896 tornado. The third building is still there, and was an operating hospital until it was closed in 1987. The complex was saved from demolition in the 2000’s and is now a (massive) condominium complex.

Firehouse #7

It’s actually chopped off in the section above, but here’s a closer look at Firehouse #7 (labeled #30). The building still stands today on S. 18th Street.

![]()

Lafayette Square is a historian’s dream, and plenty of information can be found in libraries, museums, and the neighborhood’s own website. I’ve also spent countless hours walking through it, bicycling around it, and drinking in its numerous eateries. I’d love to live in one of those “Painted Ladies” if I could, but for now I’ll enjoy repeated visits to the Planter’s House (my favorite cocktail bar in St. Louis) and happy hours at Sqwires.

Lafayette Square is also home to Square One Brewery and Distillery, the pub where I found my drink (it’s also profiled in my latest book). Square One opened in 2006 and resides in a building at the corner of Park and 18th. It’s not on Compton and Dry’s map (it was built in 1883), but Firehouse #7 is located just a short ramble away. It’s a place filled with history, even my own. The building used to house a bar named Killabrews, a place where I used to regularly blow off steam with a bunch of co-workers in the late 1990’s.

Anyway, feeling the need for a classic cocktail, I ordered a sazerac to toast Lafayette Square and its famous park. The sazerac is famously a New Orleans cocktail, but I hadn’t had one in ages. Using their own Neukomm Rye, Square One’s version is very good. And at the very least, its color reminded me of the countless house I spent coloring the brick in one of St. Louis’s most historic neighborhoods.![]()

Since so much time was spent coloring plate 39, I relied on the work of others to assist with much of the historical content. I have many people to thank for that, including Andrew Wanko at the Missouri History Museum, Andy Hahn at the Campbell House, and many others at Landmarks Association of St. Louis. Lafayette Square’s own website was also a fantastic resource. Historian Mike Jones is doing St. Louis a great service to St. Louis with his articles posted there. Finally, thanks to Jameson O’Guinn for his help with Adobe stuff.

Another outstanding installment. I always get excited when I see a notification in my email about a new distilled history post! Maddening to color I am sure, but could you imagine drawing it?

Cheers –Alan

Absolutely amazing! Your blog is tremendous–both interesting and entertaining. You should do all crafters in the US a huge service and post your map wall on Pinterest. One question–I couldn’t find plate 3 on the Library of Congress map, probably because I have old and feeble eyes. Where is it?

Thank you! I should definitely use Pinterest more for this kind of stuff. Thanks for the suggestion. Curious about your question, however. Are you needing the link to where the Library of Congress has the plates online?

No, I looked at the key for all the plates and couldn’t find plate 3. In fact, I wondered why the plates were not in some kind of numerical order. Do you know why they’re numbered the way they are?

Plate 3 is at the middle-right of the second to bottom row (between plates 6 and 4). If you know St. Louis, it’s kinda where Chouteau and Broadway intersect. Compton and Dry was originally published in a book format, and wasn’t intended to be stitched together and viewed all at once on a wall. My guess is the numbering follows how the pages are presented in the book. They start with the core downtown area and end it with less developed areas far to the west, but I have not come across any other information about the order.

So it’s the great great granddaddy of Google Maps!

Very impressive hobby you have here. Thank you for the effort. I’ve lived here for years but there’s much I’m not aware of.

Duuuuuuuude!!! That is some seriously, SERIOUSLY amazing work. I am utterly gobsmacked.

Ha! Thanks Kevin

amazing!

Looking for a view of the old St. Louis Union Depot – I have not seen a good clean image suitable for reproduction.