Here’s what I typed into Google a few days ago:

“What is that clicky thing on an Olympic bow?”

While enthralled with NBC’s archery coverage of the Rio Olympics over the past week, I kept noticing this little piece of metal (or maybe it’s plastic) on an archer’s bow flip down and “click” (it makes an audible “click”) just before an arrow was released. And I was sure Google would give me some fancy techno-archery term to describe something only what an Olympic archer would know.

Well, it turns out it’s just a clicker. Seriously. They call it a “clicker”.

Anyway, the purpose of a clicker is to let the archer know that the arrow has been drawn back enough to effectively fire it. It’s usually made of strong wire or carbon, and the audible “click” is the signal to fire away. And once again, I’m enlightened.

Actually, this little nugget of information helps explain why I am so happy the Rio Olympics are finally here. The Olympics are filled with great history, and each time I watch the games, I find myself wanting to know more. So my Olympic experience is not just watching the games. I use the time as an opportunity to flip through reference books, click-through Wikipedia, and ask Google for the stories behind the sports that are played, where they have been played, and most importantly, the people who have played them. As I figure out what a “clicker” is, I’m also learning that the South Koreans are the best archers in the world (at least in the Olympics), that humans have been shooting arrows at things for over 70,000 years, and that the only sport women could participate in at the 1904 St. Louis Olympics was in fact, archery.

And speaking of St. Louis, all of this reminds me how great it is that the city I now call home once hosted the Summer Olympics.

The St. Louis games suffer a poor reputation in most Olympic histories, but it’s still fun to know we had one. Only twenty-two cities in the world have hosted the summer games, and it’s a feather in our cap to say we are one of them. Even better, we flat-out stole the Olympics from our midwest rival Chicago, the city the games were originally awarded to. That’s a story (and a good one) for another day, but I first have to tell the story of George Eyser, a story I’ve been saving since I last wrote about the Olympics in 2012.

George Louis Eyser was born on August 31, 1870 in Kiel, Germany. His family emigrated to the United States when he was fourteen, first settling in Colorado and then in St. Louis. He became an American citizen in 1894, was a bookkeeper by trade, but other than two remarkable facts, little else is known about George Eyser’s story. The first fact is that at some point in his youth, George Eyser was run over by a train and lost his left leg. The second is that despite this tragedy, George Eyser became an Olympic champion, winning six gymnastics medals (three gold, two silver, and one bronze) in a single day at the 1904 St. Louis Olympics.

Before I get to the details of Eyser’s special day, let me set the table a little bit. A key reason why many Olympic historians believe the St. Louis games came up short is that many of the world’s best athletes didn’t bother to show up and compete. Many even use George Eyser to help make this point. If a man with a wooden leg could win gold, the guy who won silver must have been a pushover. It’s an argument that does have some merit. Getting to the middle of North America in 1904 wasn’t an easy task, and the 1904 Olympic organizers decided to stretch the Olympic events out over four months to coincide with the 1904 World’s Fair. To complicate things, organizers also broke the gymnastics competition into two separate events. One competition was held in early July of 1904, and the other in late October. As a result, many of the best European athletes decided not to make the trip. And although Germany sent a team of athletes to compete in the July competition, they didn’t stick around to compete in October.

But I believe George Eyser’s accomplishment shouldn’t be diminished. The level of competition he faced certainly wasn’t as skilled as it is today, but the sport of gymnastics was in its infancy in 1904. Despite this, Eyser undoubtedly faced athletes skilled in gymnastics. One example is Anton Heida, a 25-year old Austrian from Philadelphia who won six gymnastics medals of his own, including five golds. Heida was also the 1902 national champion in the long horse vault, and was a respected gymnastics athlete. In fact, the only event in which Heida did not win gold was the parallel bars competition. And it was George Eyser who beat him.

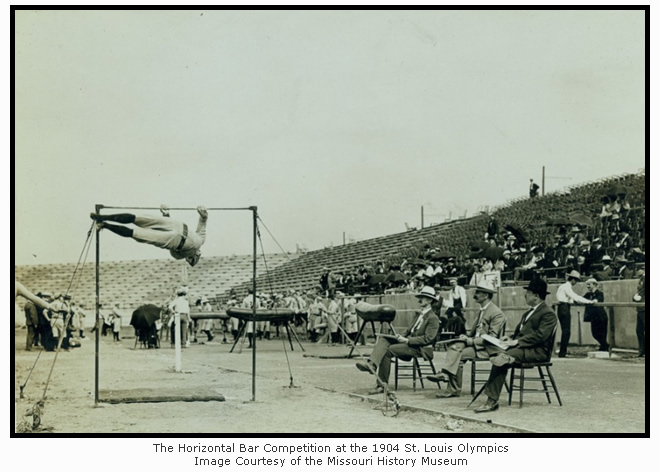

In what must have been a fascinating event to watch, Eyser and Heida also tied in the long horse vault (known simply as the “vault” in today’s Olympics), and each man was awarded a gold medal. Eyser’s performance is remarkable because unlike events that didn’t require the use of leg power, such as rope climbing or the horizontal bar, the vault competition certainly did. And the 1904 event didn’t include a springboard like it does today. George Eyser was required to launch himself over the apparatus and safely land not just once, but three times. His impressive final score matched that of a national champion who had both legs intact.

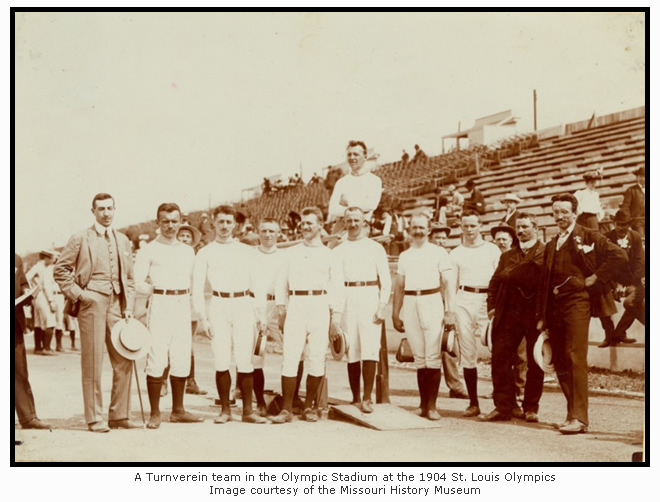

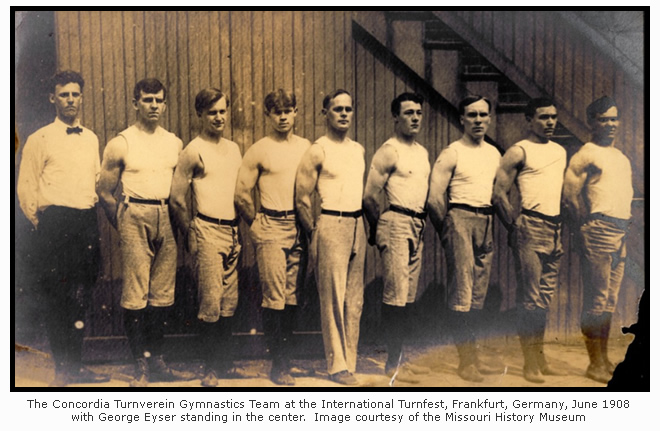

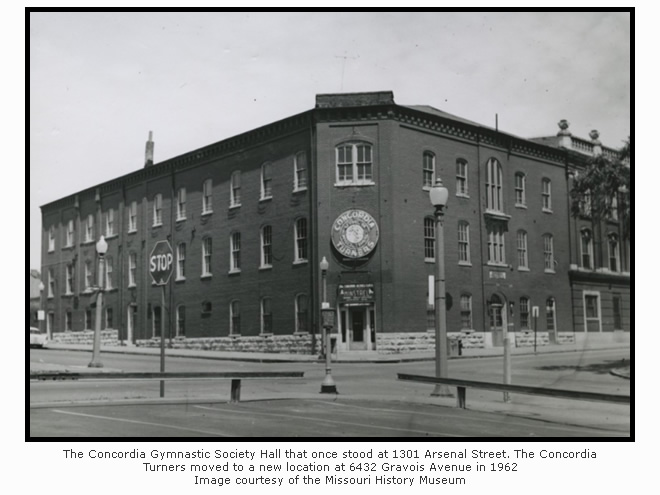

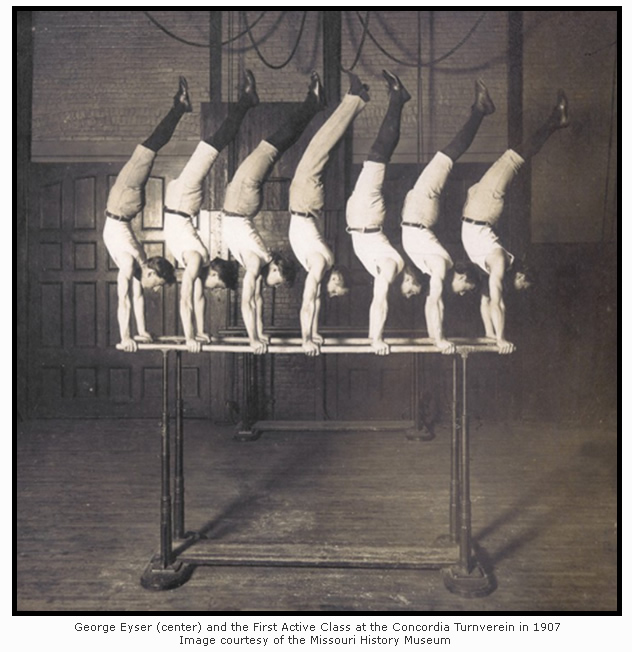

Another reason I’m inclined to believe George Eyser was exceptional is because of how popular gymnastics was among German Americans at the time. This was due to an actual gymnastic movement, or Turnverein, founded by man named Friedrich Ludwig Jahn at a time when Germany was occupied by Napoleon’s forces in the early 19th Century. Established for the purpose of cultivating health and vigor through gymnastics, the Turnverein movement came to America when German immigration was at its peak in the mid-1800’s. As a result, hundreds of Turnverein (also known as “Turner”) societies were founded all over the country. In large cities like St. Louis, Turner halls became the athletic, social, and political centers for thousands of German immigrants settling into a new life in America. More than a dozen Turner halls were founded in St. Louis, and each one contained a gymnasium filled with German athletes learning gymnastics, practicing gymnastics, and making gymnastics a part of their daily lives. It was also common for Turner clubs to participate against each other in organized gymnastic competitions and athletic meets, with members representing their club first and country second. And this is how George Eyser became an Olympian. Along with the South St. Louis Turnverein, St. Louis was represented by the Concordia Turners at the 1904 games against clubs from cities like New York, Chicago, Cleveland, and many others. In fact, no fewer than thirteen Turnvereins participated in the 1904 Olympics, and one must assume that George Eyser was just one of many with sufficient gymnastic ability to win gold.

The popularity of gymnastics among German Americans could be one reason why the 1904 Olympic organizers decided to hold two separate gymnastic competitions. The events contested in July were restricted to Turners only, and were even referred to as the “Turner Games”. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported in the days before the competition that “It will without doubt be the greatest competition ever held by Turner societies”. The Post-Dispatch also reported that the German Turnverein en route from Berlin was favored to win, but it wasn’t to be. When the German team arrived in St. Louis, it was discovered that the German athletes didn’t all belong to the same Turnverein. And since that is how the American athletes were organized, the Germans were barred from the team competitions.

George Eyser didn’t find Olympic glory in the July competition. His Concordia team finished fourth in the team event (Anton Heida’s Philadelphia club won gold), and the all-around competition included track and field events that didn’t suit George Eyser’s unique disability. Not surprisingly, Eyser finished 118th (dead last) in the 100 yard dash, 118th in the long jump, and 76th in the shot put. However, despite a wooden leg, Eyser’s time of 15.4 seconds in the 100 meter dash is certainly impressive. The winner of the event, Max Emmerich of Indianapolis, won with a time of 10.6 seconds, just five seconds faster than Eyser.

On October 29, 1904, when the second set of gymnastic events began, George Eyser’s prospects for success were far better. The October events were apparatus-only, allowing Eyser to capitalize on his upper-body strength and technical gymnastic ability. As a result, he won gold in the parallel bars, rope climbing, and as mentioned earlier, tied for gold with Anton Heida in the long horse vault event. To round out his impressive day, Eyser won silver medals in the all-around and side horse, and won a bronze on the horizontal bar. Regardless of how the St. Louis Olympics are viewed today, George Eyser’s accomplishment of six medals in a single day is an impressive one. He faced quality competition in a sport that was widely contested at the time. And it wasn’t until 2008, when Natalie du Toit swam for South Africa at the Beijing Olympics, did another Olympic athlete compete with an artificial leg.

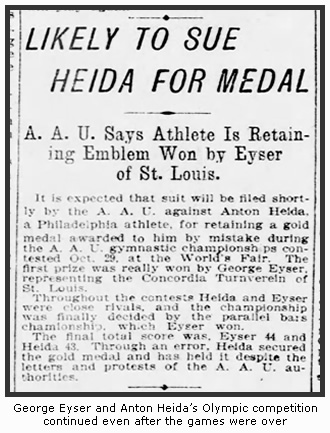

As I mentioned earlier, I wasn’t able to find much else about the rest of George Eyser’s life. But it certainly seems that his competitive fire continued to burn. Along with continuing his gymnastics career with the Concordia Turners, I found George Eyser in a newspaper article published six months after the St. Louis Olympics ended. It seems there is more to the story between Anton Heida and George Eyser’s Olympic competition. The article states that the 1904 parallel bars gold medal was originally awarded to Anton Heida as the result of a scoring error. But when the scoring error was identified and Eyser proclaimed the winner, Heida refused to relinquish the gold medal. And as the article suggests, the matter was likely headed to court. Unfortunately, I can find no record of the resolution.

But I have another week of Olympics, so I have plenty of time to keep digging.

![]()

With all the Turners jumping, swinging, and flipping in this post, I suppose I should be celebrating the Olympics by drinking something at least a bit German. But with the games set in Rio De Janeiro, I simply couldn’t resist toasting George Eyser with anything but Brazil’s national cocktail, the caipirinha.

Prior to the opening ceremonies of the Rio games, the caipirinha is actually a drink that I have never tried. I’ve been told often that is delicious, but for one reason or another, I’ve never ordered it. But as the Rio Olympics drew closer, I made sure to have a bottle of cachaça on hand.

Cachaça is the most popular distilled spirit in Brazil and the key spirit in the caipirinha. It’s distilled from sugarcane juice and has close ties to rum (but I’ve also been told not to call it a “Brazilian rum”). Anyway, it’s safe to say I became well-acquainted with the caipirinha since the opening ceremonies a week ago. I had a splitting headache the next morning, but it reminded me that I now have another cocktail for the bar book. It is a tart, refreshing drink that is not only perfect for Olympic watching, but for surviving the dog days of summer St. Louis is so eager to provide.

My caipirinha recipe:

- 2 ounces Uma Gold Cachaça

- 2 sugar cubes

- 1/2 lime cut into half-wheels

Muddle sugar cubes and lime wheels in a cocktail shaker. Add ice and 2 ounces of cachaça (or maybe a bit more if you are in the fourth hour Olympic opening ceremonies) and shake vigorously. Pour into a rocks glass and enjoy.

And don’t forget to raise your glass to George Eyser, a true St. Louis Olympic champion.

I lift an ice tea to George and to you for this wonderful history lesson.

Ha! Thank you. A worthy drink, for sure.